Marisa Miale interviews Kali Akuno and Adam Ryan, labor organizers in the south, on class struggle in the era of COVID-19. Read more about Cooperation Jackson here and Target Workers Unite here.

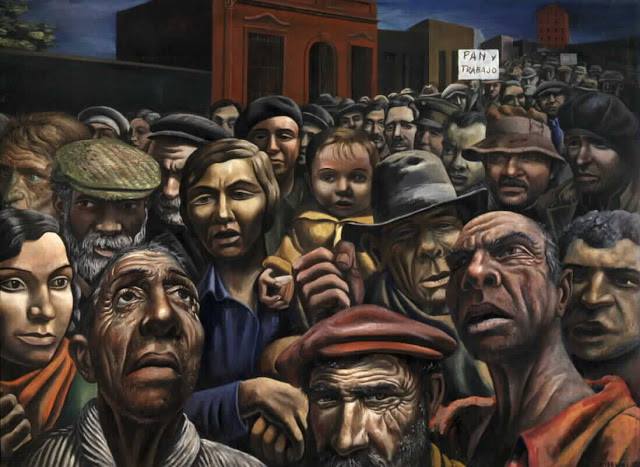

The American South has long been a forbidden fruit for organized labor. Haunted by the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow and beaten down by anti-worker right-to-work laws1, Southern workers continue to face harsh conditions. With the deep concentration of poverty across the South, COVID-19 is poised to leave a trail of devastation in its wake, disproportionately impacting the South’s Black, immigrant, and working-class communities.

Since the failure of Operation Dixie in the late 1940s, when the Congress of Industrial Organizations poured resources into organizing Southern industry and saw little success, the increasingly stagnant and bureaucratized unions of the 20th century have, for the most part, either failed to make inroads below the Mason-Dixon line or given up on Southern workers altogether. The United Auto Workers have spent years trying to organize Volkswagen manufacturing workers in Chattanooga, Tennessee2, but Volkswagen’s sophisticated and relentless union-busting has continued to ward off the UAW leadership’s shallow, business-oriented approach to organizing. Though a rising tide of worker-led reform movements like Unite All Workers for Democracy3stand to change the labor movement for the better, the union bureaucracy remains incapable of breaking the Southern ruling class.

Like a light shining through the cracks, though, a different kind of organizing has emerged in the South. Often fighting without contracts or legal recognition, insurgent and unorthodox organizers like the Southern Workers Assembly, Cooperation Jackson, and Target Workers Unite have made waves among Southern workers, relying on militant, experimental tactics and rank-and-file democracy rather than slow-moving bureaucratic machinery and top-down leadership. In the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, these organizers have stood on the front lines, charting the path toward mass action for workers across the world. In coalition with dozens of organizations across the country, they’re calling for working people everywhere to rise up on May 1st in their homes, workplaces, and communities to fight the program of austerity and mass death imposed by the state in the midst of the pandemic.

In anticipation of May Day, we’ve sat down to talk with two organizers from Cooperation Jackson, an organization building economic democracy and solidarity in Jackson, Mississippi, and Target Workers Unite, a militant retail worker organization fighting one of the largest corporations in the United States. The full interviews are below.

Marisa Miale: Hi Kali. Can you start by telling me a little bit about your background as an organizer and the work that Cooperation Jackson does?

Kali Akuno: Mm-hmm. I live in Jackson, Mississippi. I’m one of the co-founders of Cooperation Jackson. I was initially born in Los Angeles, California, and migrated here very explicitly for political work, work around the Jackson-Kush Plan4, which is a long term strategy, first and foremost centered around the self-determination of people of African descent. It’s part of a broader program of decolonization and socialist transformation.

M: What led you to Jackson specifically?

A: What led me to Jackson specifically was the organization I was in for a good chunk of my life, the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement. After September 11th, we assessed that the state and the forces of capital were going to use that to really press forward neoliberalism on a deeper level and in much more oppressive ways. Some of the work that we were particularly focused on at that time was around reparations. There was a huge reparations, global reparations movement, that we were playing a leading role in developing.

And then the other main campaign that we were focused on at that time was around political prisoners, some of the things around Mumia Abu-Jamal’s case and fighting against him being executed in the late 1990s, being the tip of the spear of that. After that, we knew just from our own history of fighting COINTELPRO and being victims of that, that this was going to be a perfect excuse to make everything that happened during COINTELPRO5, this was going to make that legal

So we kind of reorganized our plans, re-articulated a number of different things in our work, and said that we wanted to re-pivot to do a much more concentrated power building project, and we wanted to see what we can really build. This was in 2003.

We created a five-year plan, and we were looking to recruit many of our members to come on down, including myself, leave different places that we were scattered out over in Oakland, Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, Detroit to move on down to Jackson and add some skill and capacity there.

I moved to New Orleans right after the flood, as I was a national organizer of the organization at that time, to really try to focus and hone in on that effort. But that really sharpened some things for us in our minds at the time, that led us to believe we were on the right track around trying to concentrate our forces and it made us look much more deeply at the impact that ecological calamity and climate change is going to have on the black communities in the Deep South.

So we really honed in on Jackson, and made it much more important for me and others to move here and try to concentrate our energy in doing a real dual power type experiment, and that’s what we’ve been working on the past 15 years really, with the Jackson-Kush Plan.

M: Could you tell me more what you mean by a dual power experiment?

A: For us, particularly at that time, it meant building autonomous institutions and an autonomous practice of self-governance in the community. That would do two things. One, it governs itself and does a lot of taking care of basic needs, particularly in a poor community like Jackson, that they did not have the capacity and will to do, to try to meet some of those needs on our own through mutual aid and solidarity economy type work, [like] building cooperatives. Then the other piece of it was really to stop the repressive arm of the state.

That’s the notion of dual power that we were trying to build and trying to push forward with the Jackson-Kush Plan. For us in practice what that would look like from 2003 to 2012, 2014, was People’s Assemblies, I think was the highest expression of our practice in that regard, where we were bringing different forces in the community together just to make real democratic decisions on how to handle everything from supporting a lot of the elderly, a lot of work around mediating the turf wars and communal violence taking place, both in the community and on a domestic front. Those are things that People’s Assemblies specialize in. Also raising broader democratic issues around how to contain the police, how to have a counter-force to violence perpetrated by the police.

So those are all things that the People’s Assembly did well. Then at different times, it also came together real well to provide extensive mutual aid during times of crisis or, one of its best moments was doing, right after Hurricane Katrina. Jackson had a distinguishing note of being the city with the fourth highest number of folks who were displaced from New Orleans in particular and were forced to move here. They could be just dumped here. That initially created a lot of tension within the community, particularly around some of the government programs like housing. There’s not much public housing in Jackson, not anymore. What they did have was a lot of Section 8 housing.6 They moved them up in the priority list, where a lot of folks in the community had been on the waiting list for 5, 10 years. That created some real tension in the community, but the People’s Assembly did a good job of mediating that, and then providing relief to folks.

M: I want to walk back a little bit and ask if you could give a brief explanation of what a People’s Assembly is and how they make decisions.

A: The People’s Assembly model you had here, that I first had because there’s still an institution called a People’s Assembly here, but it’s unfortunately in my view turned into more of an information sharing institution for the Mayor, more so than an assembly. For us, an Assembly, it was something that was facilitated by, in essence, a coalition of forces. The group that initiated a call for it was the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, in alliance with a longstanding set of left forces in town. Which here would range from the NAACP. We had a small fraction of Communist Party and Committees of Correspondence, a few small anti-fascist groups that have been around for a while. All of them played a key role over the years, building the People’s Assembly.

It was really rooted in five particular neighborhoods where it had some real strength. Two in South Jackson, one in West Jackson, which, West Jackson is the largest geographic area in the city, but one in West Jackson and then two in North Jackson. These are all working-class neighborhoods, Black working-class neighborhoods. They would primarily meet in parks and churches, depending on the season, depending on weather. Folks would come together primarily based on different issues at their height once a month, and people would bring forth different issues that they wanted to have addressed, make a pitch or argument for. People would take up counter-arguments for. There would be a striving first for consensus. If consensus couldn’t hold after two rounds there would be a vote, and that would have to win by two thirds.

Then once the decision that was made by the group that was there, typically there would be a committee, a volunteer committee would emerge to carry out the work, that would be actually right there, people would sign up for. Then the continuing of executing that work would be handled primarily through that committee. Then the different committees that were created would form what was called a People’s Taskforce. The People’s Taskforce was really coordinating a lot of in-between times of the Assemblies, to make sure the work was carried and what folks could do, and at different times set the agenda.

I would say just for my own editorial, just so folks know, the Assemblies typically work best in times of crisis. Here, that was quite often because of being a Deep South state run by neo-confederates and fascists in the main. Both politically and socially, they were always advancing some measure attacking immigrants or queer people or abortion clinics. You name it, there’s always some level of attack which is going on even now, with COVID.

So folks would be very good in responding in defense of each other. Where we would often see sometimes some challenges and troubles was articulating what we were for, and building a degree of consensus around that. That sometimes often broke down between those who had some form of a religious or spiritual practice, those who were more either agnostic or atheistic in their orientation. So the impact of being in the Bible Belt would show up at those kinds of moments. In terms of fighting the forces of white supremacy and fighting reaction, that’s typically when it was at its full strength.

M: That makes sense. Do you want to tell me a little bit about how the current crisis is impacting people in Jackson, with COVID and everything?

A: Yeah. For lack of a better term, it’s very schizophrenic. The mayor has been trying to enforce fairly strict physical distancing type orders, and encouraging folks to take it seriously. That’s been hard because there was a bunch of conspiracy and just nonsense stuff floating around the Black community, not just here but nationally. So I know I started, even in February, was arguing with folks in different radio forums here and online. There was this notion that started getting put out in a lot of Black, Afrocentric political circles that only Chinese people could get COVID-19 and Black people were immune. I don’t know whose pseudo-scientific bullshit that is, but that’s utter nonsense. But it was very widespread, very popular.

Also combat different notions I’ve heard going in the other direction, but with the same impact, if people are true believers in Jesus, the blood of Jesus will protect them from COVID-19. We’ve been battling that.

But then on the other hand, you got the Governor [Tate Reeves], who basically has just been following behind everything Trump and the right-wing think tanks that have been pressuring him, and been in his ear, Tate Reeves has been on the front lines of trying to implement their programs and policies. It wasn’t until Florida, and I think it was six or seven of them all on the same day, they gave these weak stay at home orders but weren’t requiring that the state shut down or anything of that nature, clearly weren’t following the medical and scientific advice. But for two weeks, he was on air, on a government channel, with supposedly this liberal-type division of Church and State, which has always been a sham here, but he would be on TV for several hours a day reading the Bible in mid-March. That was his response to COVID-19. So you get a sense of how just all over the place things have been here.

We first started noticing its impact with several members of the homeless that live in our community, just a part of our community, part of our membership. They disappeared for a couple of weeks and we started asking around folks here. “Well, you know, they died.” It was like later putting one and one together, we were hearing more about what people died from, which was just unusual that they died from COVID-19. It was spreading pretty early around here.

But folks have no access to medical care. There’s no real public transportation in Jackson. So the nearest hospital from my house is five miles away, and not many people will walk there. Most homeless people, even if they do show up, the first response typically is have them arrested and then have the police determine whether they need healthcare. That was even pre-COVID-19.

So we’ve been watching that escalate. There’s at least 10 homeless folks we know about from our masking work (trying to distribute masks), and just talking to folks that we know in the community about what’s going on. There’s at least 10 people who’ve got it, none of whom have been tested, none of whom have been included in the official count of the state. But we know there’s a severe under-count of how many have been infected, and how many people have died from it here in Mississippi.

I think the under-count on this thing here is pretty severe. What we do know from what’s been counted, it’s primarily Black women who have been exposed, from primarily service work that they dominate here in Mississippi, store clerks and things of that nature that have been the most infected, and it’s been overwhelmingly Black people who die.

It’s having a serious impact here in Mississippi. Not to the degree I think of what we saw in New Orleans last month, but I think Mississippi, and Jackson in particular, I think is just starting to really pick up. I don’t think we’re nowhere near peak infection here at all. The only thing that might stop it, because there’s nothing that the government is going to do, and nothing that the medical institutions here have the capacity to do, the only thing that might stop it is nature, and that being the changing of the season, and sun killing the virus in a lot of places. So people where it might come into contact with a door or something like that, sunlight killing it.

That may be the only thing that stops it temporarily but I think our biggest fear in what we’re getting prepared for, learning from other past epidemics, that this is probably going to be like the flu in 1918 and it’ll probably last some years and be seasonal, because of some of the populations of poor Black working class and homeless population that it’s clearly been embedded in now, but this is going to be around for a while.

M: Do you want to tell me more about the programs that y’all are implementing in response to COVID?

A: Yes. So, the first thing we tried to do was what we know how to do. Many of us being veterans of Hurricane Katrina, we learned a thing or two about mutual aid and emergency relief from that experience. So we quickly got into that mode, early March. Luckily, I would say for us, with our international orientation and politics, we’ve been in dialogue with folks from Naples and Milan, at that time, who told us ‘stop, don’t do that. Unless you have the proper personal protective gear, that’s not going to work.’ They let us know that they did it in late February, responding to how it was picking up real quickly in Italy, particularly the folks up in Milan, where it’s more concentrated. They all got sick. They let us know, ‘back off, don’t do that because you’ve got to have the gloves, you’ve got to have the face mask, you’ve got to have the mask.’ Which at that time, a few of us did, but not many.

So we stopped doing that, and then we tried to repeal and to figure out what the hell could we do? Because by that time, we had figured out a couple of folks that we knew when they had died, so we knew we had to do something with the resources that we built up and amassed and the skills that we amassed. Then we got a call from one of our members about, you know, “do we have any masks or could we make some?”

We went, wait a minute, we can do that. We’ve got enough skilled folks who know how to sew. It was in like the second week of March, we pulled a team together. They started researching which would be the best mask, got the sewing machines out and started working.

Then our crew that does the 3D printing, we got some information again from Italy, that some folks in the Fab Lab network7 that we’re part of, that they started printing masks and [3D] printing ventilators. We got some 3D printers. So we got our own masking program now that’s been developed, that we’re sharing out with folks, so they can freely download it and do all those things, and hopefully use it in their communities, anybody that has those kind of tools.

And we’ve been doing mask distributions basically once a week, every Wednesday. So we’ve got another one tomorrow. It could be about 120 a week that we give out of the foam mask. The 3D printed masks, we’re doing about, I think now about 20 of those a week. We make a distinction that the 3D printed masks go primarily to healthcare workers. So we can only do a certain limit of those and they’re much more efficient and more medical grade. So trying to give those to a lot of the nurses and stuff in particular, so they don’t get infected and they can help defend other people’s lives.

So we’ve been doing that, and since that’s kicked off in the last two weeks, we’ve been ramping up a food distribution program. So it’s not a full mutual-aid practice that we would normally do, but things that we can do safely, given the kind of protocol that we’ve set out. So those are the two emerging community responses that we’ve been doing, and now we’re trying to ramp up the political response, and that’s calling for May Day actions on a mass scale, that we fought for, that’s what that’s about.

People were saying, look, there’s more people who die from the flu every year, or more people who die from malaria. I was like that’s true, that’s correct but those are things that are calculated very much so by the health and insurance rackets that exist on a global scale, so that’s acceptable death for capitalism. This is something new and outside the bounds, so they don’t know how to factor it in yet. I always kept telling people, let me speak to you from more of a personal connection, tragedy for one of my best friends, died from SARS 10 years ago, which is another type of coronavirus.

M: Right.

A: Fortunately, none of our members that we know of at this point have gotten sick. And nobody’s died. Now I know over 50 people throughout the world who have died personally. It impacted me in that way. But none of our folks, I think, from us taking precautionary measures, none of our folks have gotten sick.

M: I’m glad to hear that. Do you want to tell me about your political response now and the May Day actions?

A: Yeah. The thing that really kind of propelled us in motion was this rush to put people back to work, that we first heard on a state level. We didn’t have the evidence then that we have now, but we suspected that this thing was killing Black people and Latinos at a disproportionate rate. That was our suspicion in March.

That means we need to take, not just a community response, we got to take a political response and try to send a clear message that we’re not going to die for Wall Street, we’re not going to die for deep pockets. We’re going to try to reach as many of our people as possible to say, no, this is time to put out some maximum demands, basically.

They’re not gonna provide hopefully the basic things we need. Gloves, masks, no protective gear. There’s no way in hell that people should go back to work. We have been agitating for that in our own community. They had to shut stuff down here, so a lot of things would just open in March. And then when Trump got on the bandwagon, saying that he wanted the country to all open up again on Easter.

And looking at the overall conditions and the number of wildcat [strikes] that were already popping up at that time. This would be the perfect call to start building toward a general strike in this country. Because the things that we were seeing, like in February, most folk just shake it off, any notion that universal healthcare could be a possibility. Now, that’s like a basic demand. So, the situation has just elevated people’s consciousness to a great degree. And we were like, let’s try to play a role, step into their void. Let’s not let the Right define what the feeling is, we need to from the Left, try to define it.

I don’t think we made it clear enough in that first statement8, that we didn’t think May Day could be a general strike. So that’s why we’re calling it towards a general strike. We need to take mass action on May Day, send a clear message. But we got to work our way up towards that. This is going to be a protracted struggle.

So the coalition we’ve been pulling together, and we’ve joined forces with CoronaStrike and General Strike 2020, who were out before us, earlier than us, we’ve kind of all come together, you know, joining messages, working together, trying to build some links, plan out all the different activities that are going to happen on May Day.

So that’s what we’ve been focusing on through the last two weeks. I see a lot of momentum going. Trying to put it all together, I think is going to be one of the next major challenges. The first critical thing is getting people in motion. Say hell no, we’re not going to work, we’re not going to shop, we’re not going to pay rent, we’re gonna shut it down, navigate all the hills of that.

We’re working to start building levels of self-governance in our community. To really balance out the system. That’s ultimately what we’re trying to get through that. And eradicate it, no ands ifs or buts. But easier said than done. We got to move millions of people to that program. So that’s something that we will keep pushing for on our end. Struggling for that clarity and programmatic unity. It’s going to take time.

But I think that if nothing, this pandemic I think has exposed the sheer exploitative nature and brutality of the system. So I think there’s many millions of people who are waking up, as this hit home with millions of people now being unemployed. You know, millions being cut off from their healthcare. I think the inhumanity of the system I think has become apparent and people are going to be demanding a whole different set of social relations on the heels of this, and how we fight that out is going to be critical.

M: The last thing I want to ask is what the best way for workers across the country to get involved in this movement is?

A: For workers, particularly essential workers, you got to start with organizing your fellow coworkers. So there’s an inward look that folks first have to do, if they’re being honest. Because what we’ve been stressing in our calls is kind of arming them to agitate, to do a level of education and inspiration. But the real actions have to take place by decisions made by workers at the point of production. I know, here we can have an impact in Jackson and we plan on doing that. But folks in New York, Atlanta, Houston, Detroit, everywhere, it’s themselves who have to make that determination of what level of risk they’re willing to take, and that’s going to be determined by what level of strength or level of unity or solidarity they have with their coworkers. So our thing is to uplift actions, like wildcats that have been done and rouse people’s imagination, let them know that a fight like this is possible.

And so to uplift that direct action to show that we can get some immediate results. With deeper levels of organization, you get a lot of results. One of the things that we’ve put out there is encouraging folks to organize to seize the means of production and democratize it, turning it into co-ops, or things of that nature. We’ve seen some level of initiative with that, with folks saying in some of the auto plants, they want to start producing masks and ventilators and things like that. But I have to stress, you first got to start with organizing their coworkers at the point of production. And try to move as a team, don’t move alone. That’s how they can isolate you. When you organize with folks move as a team.

M: Great. Okay thank you so much for speaking to me, this was a really great interview.

A: No problem.

Marisa Miale: Hi Adam! Thank you again for agreeing to the interview. Could you start by introducing yourself for our readers, telling us a little bit about your background as a worker, and explaining how you got involved in organizing at Target?

Adam Ryan: Yea, my name is Adam Ryan, born and raised in southwestern Virginia, the Appalachian region of our state, specifically in Christiansburg. We have a lot of the same problems as other parts of Appalachia in terms of poverty, drug addiction, shitty jobs and slumlords, but we have two local colleges that act as a sort of buffer to all those issues, so while we do have more infrastructure developed here than in other parts of Appalachia, that infrastructure is only geared towards the students and the colleges and not the local working class. Some folks have even designated our area as “Metrolachia” because of the college system and the huge import of wealthy students and their families largely coming from the DC suburbs in northern Virginia. There’s definitely animosity between the local working class and these students who basically get to live in bubbles the colleges work to cultivate, so they don’t have to see or really know what it’s like being a local living in the area.

I got hired on at our local Target back in 2017. The store has been here for over a decade. My family has worked there and many other similar shitty low wage, no-benefits jobs in the area. You either work in the service sector or manufacturing in the New River Valley. I specifically went to Target after our collective New River Workers Power was conducting social investigation with local working-class families primarily through canvassing our local trailer parks. That’s how we got the lead about the abusive boss Daniel Butler at our local Target store. We hit a roadblock trying to organize working families against these trailer park slumlords and decided to switch gears to labor organizing.

I had prior experience with labor organizing back when I was an IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) member and went through their Organizer Training 101. This was back when I moved to Richmond, Virginia in 2010 when I was organizing Black working-class families disproportionately affected by our state prison system. We started a group called “SPARC” (Supporting Prisoners Acting for Radical Change) as a joint initiative between ourselves as workers in southwestern Virginia and the New Afrikan Black Panther Party – Prison Chapter headed by comrade Kevin ‘Rashid’ Johnson, who’s a Richmond native. This was all before New River Workers Power had formed. We had an exclusive focus on prisoner organizing at the supermax facilities at Red Onion and Wallen Ridge state prisons located out in Wise County. It was when I moved to Richmond with others in SPARC to better serve those most affected by the prison system that I got tied in with a recently-started IWW chapter. We saw an opportunity to tie the two efforts together and basically were doing a proto-IWOC campaign of sponsoring the prisoners we were organizing as SPARC into the IWW as union members. We figured it would at least give us some legal room to not have our mail tampered with since it was official union business with our fellow workers in the state prisons. As SPARC we got our mail censored all the time and were designated as a group trying to “promote insurrection” in the prisons. This all came to a head when we had a series of prisoner hunger strikes we helped organize and support back in 2012.

Long story short we were stretched too thin trying to take on the largest, most well-funded department in the state of Virginia with only a handful of organizers scattered across the state, we also were young, in our early 20s with very little organizing experience under our belts and it became too much, so we transitioned to organizing locally within Richmond city itself (still a monumental task). I spent several years trying to do some workplace organizing as well as community organizing around school closures, tuition hikes, and police brutality, but eventually ended up homeless since the shitty service sector job I had at CVS wasn’t enough to cover my rent. I never had enough funds to even afford a rental unit with a formal lease. I was always living in illegal housing and paying slumlords under the table, so it was easy for them to push me out, and I had nowhere else to go but to return back to my hometown. That’s when I started up New River Workers Power and all the local organizing we are doing here now, including the Target organizing campaign.

M: Could you tell us a little about the history of Target Workers Unite and the kind of work y’all do?

R: We launched Target Workers Unite at the beginning of last year initially as a fail-safe to our attempt to collaborate with this NGO called “Organization United for Respect at Walmart” otherwise known as “OUR Walmart” – which now goes by the name “United For Respect.” This organization was initially started as a front for the union United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) back in 2012. It was a very similar model the “Fight for $15” front started by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). Their goals weren’t to formally unionize these shitty low wage service sector jobs from Walmart to McDonalds, but rather to build a lot of PR to then funnel that energy into electoral politics and aid the Democratic Party in the hopes some reforms could be passed through state and national legislatures.

Workers were instrumentalized to become spokespersons and advocates rather than trained as militant organizers who engage in collective direct action to win concessions from the bosses. By the time United For Respect (U4R formerly OUR Walmart) reached out to us they had split from the UFCW after their union president cut funding to their front. The executive directors then found new funders through the Center for Popular Democracy, also a front largely funded through these bourgeois philanthropist foundations and trusts like the Ford Foundation, George Soros’ Open Society Foundation, etc. They scour the internet and news outlets to see any manifestations of worker activity outside the unions and try to bring those workers into their fold, that’s how they found us after our first wildcat strike against our local abusive boss.

I didn’t intend the wildcat strike to transform into a national Target worker organizing campaign, but that’s how it organically developed. The paid staff of U4R reached out and wanted to incorporate us into their efforts, saying they wanted to “organize all retail workers, not just Walmart workers,” hence the name change. But after struggling with them for over a year on what organizing workers actually meant, I found out they already had their agenda formed – which wasn’t determined by the rank and file workers, but rather the paid “professionals” whose strategy is essentially dictated by the bourgeois foundations that fund their NGO. We wrote a full statement of what that experience was like and why we had to launch Target Workers Unite if we wanted actual rank and file Target workers to be trained up as organizers and take direct action in our stores. After seeing what tools they utilized and what “organizing” looked like to them I also figured they weren’t really doing anything that drastically different from what we had been doing, minus the huge source of funds and paid staff they could rely on to do the work for them.

I should clarify that we weren’t trying to organize along the lines they were – in terms of trying to take workers out of the workplace to become public advocates pushing reforms and teaming up with opportunistic politicians to push a reformist agenda, but more-so their heavy use of digital organizing techniques through social media. That is probably the only thing I feel I may have learned from them after participating and trying to push for rank and file worker organization in our stores. Maybe a slight refinement of what we had been doing, but there wasn’t really that much substance behind their efforts beyond trying to produce high-quality propaganda that looks good in the press.

I figured if these “professionals” could bullshit their way into a “legit” labor organization, then why can’t us rank and file workers do it ourselves? At least we would have autonomy and the ability to determine what path we take vs constantly having to struggle against their paid staff over what constitutes real organizing or what are we ultimately trying to achieve as workers. I really was turned off by their default social democrat ideology that drove their slogans and abstract demands they had no real leverage to realize. Like when Bernie Sanders came out talking about getting workers on corporate boards as a policy in partnership with this NGO that to me was the epitome of their politics and endgame. Why should we be trying to emulate the European mainstream unions when they’ve run into deadends themselves when trying to build workers’ power that isn’t dominated by capitalism? If we are going to make pie-in-the-sky demands, we might as well advocate workers’ control and taking over the shopfloor, eliminating management and the capitalist division of labor. At least we send a clear political line to workers by doing that rather than the default opportunist, class compromise politics they were pushing, which was tolerable for their bourgeois funders.

In terms of the work we do now it’s a combination of digital organizing, going into the social media spaces we know Target workers are at and agitating them to organize directly about shopfloor issues and corporate-wide issues over things like unstable scheduling, lack of hours, lack of benefits, ageism, favoritism, and all-round poverty this corporation purposefully enacts for the purpose of control over our workplaces, dividing the workers, and repelling any efforts by workers to capture a larger share of wealth generated within the company. We work to find workers who are most motivated to take action in the stores and show through direct action we can win smaller demands, prove our competency and leadership and build morale that there is an alternative to how the jobs are structured, what can workers to to change the conditions and boost morale which shows workers we don’t just have to accept things as they are. A lot of this is class struggle on the ideological level, most workers don’t know their labor rights as defined by the NLRA, they don’t know how to build a labor strategy to organize and win concessions, we have to build that culture from scratch and that’s just where we’re at, even in the middle of a pandemic.

M: It sounds like it’s been a long road to build worker power for y’all. Can you tell us more about some of the shopfloor issues you’ve been organizing around the solutions you’ve put forward to them?

R: Management abuse and worker disrespect have been the most prominent for us. But we’ve also organized against fascism, specifically at my store, by pressing to get a local notorious member of the alt-right banned from our premises. It was definitely a heartwarming experience to see so many of my coworkers willing to sign on and say we don’t want fascists in our space, they are a safety hazard to our coworkers who are LGBTQ, Jewish, workers of color, and leftists. We didn’t fully escalate on that campaign, but this fascist Alex McNabb decided he wanted to try to mess with us over this and did what any reactionary would do and call up our management to complain he was being “harassed”. Our unity was strong enough that management didn’t do a single thing to us for utilizing our labor rights to organize for a safe workplace. That fascist hasn’t dared to come back to our store since. We’ve done a lot of mutual aid for coworkers too, fundraisers for LGBTQ coworkers trying to get top surgery, showing support for LGBTQ coworkers by distributing and wearing trans pride bracelets in the face of Trump’s announcement to remove certain protections for LGTBQ coworkers on the basis of discrimination.

A lot of what we’re doing is base-level stuff of trying to educate coworkers at my store and across the country what are our labor rights and how to exercise them in a strategic way without getting caught up in legal battles, especially outside the context of a formal union. So many workers view unions as service-based in the same way they pay for a good as passive consumers and expect the “officials” to fix their problems for them. So we have to cultivate that new worker culture of solidarity that’s only surviving in small pockets across the US right now. It’s not a living practice for the majority of US workers.

I’m not going to pretend we have this huge network with worker committees across hundreds of stores, but we do have a lot of coworker contacts across the country we’re actively working to engage and trying to train up to essentially become “shop stewards” in their stores. When you get the reputation of being a worker who can get issues on the shopfloor fixed without having to go to management and coworkers see you have knowledge and experience in exercising these rights they come to you with issues, much like a shop steward would function in a formal union.

The big joint effort we’ve been working on across Target stores was our Target Worker Survey project. Every year the corporation has us take their “Best Team Survey” which is really superficial and doesn’t allow workers to elaborate on how they feel about their jobs, nor do workers necessarily trust it enough for them to be honest, especially when their store managers press upon them to answer in a positive way or stand behind them as they take the survey. Us workers crafted our independent survey all by ourselves, with over 60 questions to get an understanding of what life is like for Target workers both on and off the job. We got over 500 responses from across at least 380 stores in 44 states, the results weren’t surprising, but also very condemning of Target. We’re actively working to expose what work conditions are like at our jobs and working to push back on the hegemony Target’s PR wing has in making it look like it’s all honky dory at their stores and distribution centers. We’re working to counter their propaganda with our own based on the accounts of workers themselves. Out of that survey we crafted a Target Worker Platform which was again based on the responses we got from Target workers on what they think we need to make our jobs something we can live on. COIVD-19 has sort of put that on the backburner now and we’ve had to develop an emergency petition calling for more safety and compensation for us Target workers since we are at such high risk of exposure to the virus – in large part because Target doesn’t want to take the right measures to limit foot traffic in our stores.

If you’ve ever worked in a public-facing job where you have to deal with consumers you know they have their own narrow interests in mind and that usually means them being disrespectful and inconsiderate of us Target workers. For instance, it’s not uncommon for us to find half-eaten products on the sales floor, or used tissues stashed around the store, let alone practicing social distancing, respecting our personal space as workers, and making unrealistic demands upon us because they feel entitled to “customer satisfaction.” These recent waves of protest over the economy being shut down are really indicative of that selfish attitude, Americans don’t like being told they can’t do whatever they want as consumers, it’s the trade-off they got instead of things like worker power or a social safety net, let alone political agency which doesn’t relegate them to a passive role.

Online organizing has been a huge component to what we do as well. There are a lot of Target worker social media spaces that we constantly agitate in to make workers aware we even exist and bring the ones who are interested in organizing into the fold of Target Workers Unite. Social media is a crucial aspect of labor organizing these days, if you’re not using it, you’re missing out as an organizer and worker organization. Recently we’ve started building relationships with Shipt drivers because Target owns Shipt, it’s basically like instacart or other gig worker jobs where they shop the items for a customer and deliver it to their homes. By connecting with these folks we get a much better understanding of Target’s strategy and vision as to how they’re transforming our work and also responding to market forces and competitors like Walmart, Amazon, and Kroger. We also are just going to be stronger by organizing along the supply chains because each sector of workers has knowledge of their operations and helps us counter the bullshit narrative Target likes to put out there to the general public. One of the next steps for us is to establish contact with the workers in the Chinese factories where the majority of the commodities we sell are manufactured.

M: Could you tell me more about how COVID-19 has impacted Target workers, and how you developed the emergency petition?

R: Target workers and their families are beginning to contract the virus, it’s not surprising considering the corporation isn’t restricting foot traffic in a serious way, they instead leave it up to the discretion of the customers to engage in best practices, but if you’ve ever worked in a public-facing job like ours you know when people assume the role of a customer they become very entitled and take offense to being regulated on their shopping behaviors. We need proper administrative controls which don’t rely on the discretion of consumers. The corporation knows what it’s doing by leaving it up to customer discretion as to whether or not they behave in a way that actually respects us as workers and prioritizes our safety. They rather make sales over our concerns for worker safety.

We developed the petition very quickly after the national emergency was announced, reviewing what practices other countries had engaged in to minimize spread and contamination, as well as reviewing the recommended protocols from organizations like the CDC and OSHA especially towards healthcare workers. Because we weren’t seen as essential workers nor respected as essential prior to this, many people were overlooking our needs as frontline essential workers because we usually aren’t seen as “real workers” nor having a “real job”, therefore why should we be considered for such things? It’s a contradiction that has only sharpened as this has progressed and more and more workers are realizing how vulnerable we are, how much we’re just sitting ducks at our jobs as we have to rely on customers to be considerate of us and our needs.

One thing we notice about Target even before the pandemic is how quick they are to try to route us and defang our demands by issuing press releases to the public which at least gives the appearance they are going to address safety and compensation concerns. They are very good with the smoke and mirrors, they even have some workers believing in their bullshit. But in a way we have to be thankful that capitalists can never meet our needs in the end of the day because the nature of capitalism will never permit that.

M: I think that speaks to what essential workers across the country are feeling right now. Can you tell me more about the action you’re taking on the shopfloor to respond to COVID?

R: We’re calling for a mass sickout across Target stores and distribution centers. We want to show Target us workers are not ok with their feet dragging on rolling out more safety precautions we’ve been pressing for since the announcement of the national emergency. Beyond this action we’ve been doing the same thing we were doing before all this, educating our coworkers on their labor rights, working to build out shopfloor committees, and pressing our management to respect us or we’ll escalate and make their lives hell.

M: Hell yeah. How is the crisis impacting the shopfloor committees and their ability to organize?

R: To answer your first question, its caused more workers to see the need for independent action, so we are in a good position just by making our presence known and workers reach out on what they can do about the issues at their stores. At my store I’ve been helping some new members of our store committee to take on issues of favoritism and disrespect, those everyday workplace issues are still in place despite the virus, the virus has just exacerbated it all and pushed people to the point of being fed up and wanting to fight back.

M: Do you have a vision for how COVID-19 will impact Target Workers Unite in the long run, and how it will develop after the virus subsides?

R: I think this virus has lit a fire under people’s asses and those who aren’t totally brainwashed by the corporate narrative see that if they don’t take independent action then nothing will ever change and corporate will only do the bare minimum to “protect” workers. A lot of workers are seeing they are being left high and dry, that’s an opportunity to consolidate more workers into our network. We should emerge from this action and this pandemic stronger than when we went in and it already looks like that is playing out just by the rates or participation in our sickout action for May Day.

M: Can you tell me more about the shift in consciousness for workers who weren’t active before and want to fight back now?

R: The shift hasn’t been huge, but it’s happening. I would say it’s the vanguard of workers who have been fighting to raise awareness and educate their coworkers on the safety issues we face and to push back on the corporate narrative which tries to lull them back to sleep. The contradiction is that many workers were black-pilled or primed by various authority figures on how COVID19 isn’t that serious and people are overreacting, so we’re already having to fight from the opposite end in challenging those reactionary ideas propped up by billionaires. We have to be the militant minority that pushes the rest of the working class forward, even if a bunch of them may resent us initially for breaking this unprincipled labor peace with the corporate executives.

M: What lessons do you think workers across the country can take from Target Workers Unite about organizing during COVID-19?

R: I think the lessons are that while this moment has definitely spurred worker action the working class is still a class-in-itself rather than a class-for-itself. Many are still caught up in the corporate ideology, remain passive, and don’t view their workplaces as sites of struggle. We have to operate as a militant minority and work to reconstitute the working class as a subjective force able to effectively fight capitalism and these corporations. This is a good beginning for that.

M: Thank you so much Adam! Perfect note to end on. See you on May Day.