Stephen Boyce argues that the KPD’s failure was due to its inability to recruit women in the masses.

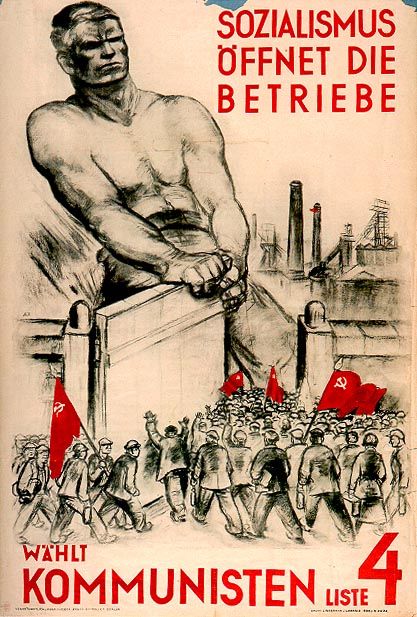

“Left-Wing” Communism, An Infantile Disorder was one of Lenin’s most well known, studied, and cited works in the international communist movement. The above quote, however, was not as popular as those describing the “iron party steeled in the struggle” representing the best of the working class and which was “capable of watching and influencing the mood of the masses.”1 During the 1920s and early 1930s, The Kommunistische Partei Deutschland (KPD) was the leading example of such an “iron party” and was the largest and most militant communist party in the world (outside the Soviet Union). Despite this, it failed utterly to stop the Nazi seizure of power and was then quickly destroyed as an effective political force. Observing these events, the French philosopher and political activist Simone Weill lamented “…the crushing and unopposed defeat of the German workers.”2

Why was KPD destroyed? What was it about the “the mood of the masses” that it did not see and could not influence? To ask these questions is to enter into the debate about the phenomena of Adolf Hitler and Nazism and thus contend with both popular culture mythology as well as the Cold War–derived fixation with “totalitarianism.” To pursue a gendered reconstruction of the KPD is also to confront the Historikerinnenstreit and make a judgment on the inclusion and participation of women in the furtherance of Nazism. The failure of KPD to win women was a key aspect in their defeat as a political party and their destruction as a social force. Conversely then, the ability of Nazism to gain the mass support of women was critically important for their ability to construct and operate the Third Reich. Each of these two theses is, in fact, the mirror image of the other.

It is one of the great ironies of women’s history that in Weimar Germany the communists, the party most adamant about women’s rights and most vocal in the call for women’s emancipation, would be an electoral failure among the majority of the nation’s women voters. The irony is compounded by the fact that “the only violently anti-feminist party in Weimar”, the National Socialists, would gain the mass support of women voters from 1930 on.3 Although it was not a uniform practice in Germany, votes were sometimes tabulated by gender, and from this data it can be shown that those parties that gained the most from women’s suffrage were (in order):

Center party (Catholic);

DNVP (Conservative);

DVP (Nationalist).4

In his analysis of the gendered vote in four cities from 1928 to 1933, W. Phillips Shively showed that the Nazis were gaining the most among women and that in 1933, they were capturing the highest percentage of the female vote in Protestant-majority cities.5 By contrast, in the crucial presidential campaign of 1932 when KPD leader Ernst Thälemann polled 15% of the vote nationwide (to Hitler’s 30%), the communist standard-bearer “received a smaller share of the total female vote than the of the total male vote in every district where men and women voted separately.”6

The statistics of the women’s votes are easy to obtain but the underlying reasons for this phenomenon are much harder to discern. Was it that the extensive list of feminist ideals in the party platform was not “systematically promoted” as alleged by Helen Boak?7 According to Julia Sneerington, there was no correlation between the emphasis on women’s issues and the support a party received from female voters. For most of the Weimar period women showed a remarkable consistency that favored religious parties first and, after that, the less radical option within the same “class milieu.” For the KPD it meant they were losing votes from proletarian women to the ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD).8 This consistency persisted after the war, even in the Soviet zone of occupation where a revived KPD worked diligently to secure the electoral support of women. Their simple platform promised secularization, expropriation of Nazi property, and women’s equality. Once again women favored “moderate, and, especially religious candidates.”9

Robert Wheeler, in an article on women in the Independent Social Democrats (USPD) in the early ’20s, made an attempt at some tentative conclusions as to why the KPD had problems with women even among the left-wing activist base.10 His study focused on the debate over affiliation with the new Communist International, which eventually tore the USPD apart. The process of acceptance by Moscow included the strict acceptance of rules and a degree of external guidance which the most prominent women in leadership positions rejected; they then rallied a majority of the female rank and file to support them. Wheeler felt that the militarized rhetoric of the Bolsheviks and the image of the Red Army appealed to men whereas women were more anti-war.11 Wheeler also felt that this whole debate injected a mood of intolerance and intense sectarianism absent from women socialists who continued to try and work across organizational boundaries. While much of this is speculative, he did advance a theory of “relative deprivation” as a model for why women came to such different conclusions than their male comrades. Conditioned by society to be patient and long-suffering, women tended to be more moderate and passive in their politics than men. This was not only true in society but also within the radical labor movement.12

If Wheeler was right then the dogmatic and militaristic leadership of the Communist International transformed German communism for the worse. Apart from the devastating impact on the ability to appeal to women, this has been the dominant judgment of historians on the KPD, whereby the party was a victim, first and foremost, of the Communist International. In this model, the KPD was so thoroughly Stalinized that there was no space for local adaptation or autonomous decisions.13 The failure of the party, then, derived from its lack of any agency with which to maneuver in response to German conditions. The main villain of this story was the Soviet hatred of social democratic parties and the shrill practice of categorizing these non-communist leftists as “social fascists. ” These sectarian attacks prevented unity on the left, thus ensuring Hitler’s triumph. For this critique, the overriding problem is that a communist party existed at all and by its existence caused the disaster that followed.

Did the fault of the KPD, and the source of it weakness among women, derive from the external source of the Comintern which was itself dominated by Stalin and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union? A recent study by Norman LaPorte on Saxony has forcefully challenged the prevailing belief that the KPD was a bolshevized puppet lacking any autonomy in its local structures and political work.14 His conclusions are supported by earlier research on the Wedding District of Berlin by Eve Rosenshaft15 and Chris Bowlby as well as Richard Bodek’s examination of the communist theater groups in Berlin.16 As regards the Comintern’s 1928 policy towards “social fascism,” Bowlby showed that this divisive doctrine was actually downplayed by the KPD press until after the events of May 1-6, 1929, when the police, under the authority of the Social Democratic government in Berlin, gunned down workers and innocent bystanders in response to a May Day march.17

Locating the weaknesses of the KPD’s practice to an external cause shifted the blame to Stalin and Stalinism for the ultimate failure of the SPD and Weimar itself and ignored the other causes from within the German socialist tradition. It was Rosa Luxemburg who wrote the founding manifesto of the KPD, and in it she fundamentally underestimated the strength of the SPD government and its ability to employ the Freikorps to maintain itself in power.18 As the socialist saviors of capitalism and the enablers of a reactionary judiciary, an anti-democratic and militarized police, and an army independent of civilian control, the SPD did more to weaken itself and discredit its regime than anything the Communist party was capable of doing. Commenting on Weimar just before its collapse, Simone Weil wrote:

“The communists accuse the social-democrats of being the “quartermaster-sergeants of fascism’ and they are absolutely right. They boast that they are a party capable of fighting fascism effectively, and they are unfortunately wrong.”19

Communists were certainly incapable of mobilizing women to assist in that fight against fascism and it could well be that their insistence that “gender equality was a central part of its larger revolutionary agenda” was largely to blame.20 If so then it must be acknowledged that this tradition also derived from Luxemburg and her demand that proletarian feminism was component of (and subordinated to) the class struggle. It was true, as further argued by Sneeringer, that the KPD

“…preached female equality as integral to a just society but because of their conviction that democracy was a sham, they constructed an image of the political woman who was less a citizen than a loyal fighter in the proletarian front.”21

It was equally true that Luxemburg and Liebknecht were the initial leaders of that front, and set the tone of struggle well before Lenin, and then Stalin, took control of the international communist movement. The KPD as a political party, and German communism as a social movement, drew its considerable strength from unskilled and semi-workers, the unemployed, and radicalized intelligentsia because of its uncompromising commitment to revolution. This commitment was also its biggest weakness for reasons that had nothing to do with the Communist International or the twists and turns of Soviet foreign policy. The promise of revolution, which so inspired the poorest workers, also frightened the middle class and alienated women of all classes.

The weaknesses of communism existed simultaneously with the growing strength of the conservative, nationalist movement in Germany of which the Nazi Party was the most dynamic component.22

To fully gauge the failure of one, it is necessary to look at the improbable success of the other. The ability of the Nazis to incorporate and use women on a national scale set them apart from the failure of the KPD to expand its base of support beyond proletarian men in the most industrialized regions of the country.23

Hitler’s attitude towards women was ambivalent in that he did not rail against them in public but instead extolled motherhood and the family (while occasionally denouncing prostitutes). In private, the Führer’s misogyny was blatant as he described women as “petticoats” whom it was worthless to attack publicly.24

From the very beginning, however, women were involved in the Nazi Party. According to the police report on the mass meeting where Hitler seized control of the NSDAP in 1922, there were 50 women in attendance (out of 350 total). As the party grew throughout the ’20s, William Burnstien’s analysis of the social origins of the NSDAP show that a disproportionate share of young, unmarried women from the middle and working class were joining the party and doing so at a much higher rate than young, unmarried men in the period 1925-1932.25 He attributed this phenomenon to the party’s call for married women to leave the workforce which would benefit unmarried women already employed or living in areas of high unemployment. Small as a percentage of the population as party members were, the growing presence of women as members or supporters indicated an ability to make inroads into the larger society watching the Stormtroopers march. On these marches, women “cared for SA men, sewed brown shirts, and prepared food at rallies.”26 Most importantly these women provided an “ersatz gloss of idealism” for those engaged in brutalizing their many enemies. These faithful auxiliaries included not just the members of the Nazi women’s organization, but also those outside the party including many whose husbands were members.27 In this miniature version of the Volksgemeinschaft (the “people’s community”), the sexes dutifully played their separate roles as fighters in the racial front against communists, “international” socialists, and Jews.28

What was the attraction of this contemptuous misogyny to the women who followed, voted for, and then supported a regime based on bigotry, discrimination, and racial nationalism? What attracted women to a party that epitomized hyper-masculinity and thuggish aggression? Of all the reasons that can be surmised, one constant was the fear of socialism and especially hostility to the Communist Party.

In her study of women in Germany, Claudia Kuntz described several activist women in the NSDAP ranks who exemplified this embrace of Nazism as protection against the “other.” For Elsbeth Zander, the first prominent female Nazi, the main dangers to Germany were “socialists and socialites.”29 In the case of Irene Seydel, a successful organizer from the industrial region of Bielefeld, the NSDAP was the only political force that “would be strong enough to prevent a Communist overthrow.”30 In her study of “women denouncers” who provided information to the Gestapo on enemies of the state, Joshi Vadana noted that most of those being denounced were Communists.31

For Koontz, Nazi women willingly embraced a subordinate position in a movement dedicated to the masculine exertion of a racial community in which women would be both protected and mobilized in their domestic sphere of home and family. For many of these women, what they most feared was the threat of socialist egalitarianism and a future in which the world was no longer organized according to sharply differentiated sexual poles. If the Nazi movement allowed some small space for women’s independent political activity (because the men considered their work so unimportant), this same movement reinforced a bi-polar world with absolute certainty as regarded the positions of male and female. In the words of the Hitler Youth Leader,

As boys aim to be strong, so girls aim to be beautiful…, something which the harmonious development of the body is intrinsic… They (girls) can dance and be happy, but they should understand that they will have no private lives; rather they will remain a part of their community and its exalted aims. Girls will willingly approach their future destiny as mothers of the new generation.32

The willingness of the “girls” in the Bund Deutsche Mädel (BDM) was so ardent that the organization acquired an aura of sexual licentiousness, resulting in the mocking reference to its initials as standing for bübi druck mich. According to LeBor and Boyes, over a thousand of these young women returned pregnant from the 1936 Nuremberg Rally, thus fulfilling the Gertrud Scholtz-Klinks admonition that while “every woman can not get a husband, every woman can be a mother.”33

While Wheeler’s theory of “relative depravation” may be seen as an explanation for women’s rejection of the Communist Party, it does not explain the allure of the Nazi Party. The explanations for that success are dominated by the notion of “seduction” and “totalitarianism” in which Hitler first seduced a nation by his charisma and then set up a police state which terrorized the population into continuing submission. What this model does not explain is the degree to which the Nazis maintained their popular support apart from the reliance on secret police and, by contrast, the failure of a very resilient communist underground to pose any real challenge to the regime. A look at the statistics of repression in Nazi Germany compared to the later German Democratic Republic shows that the weight of police surveillance was much less under the Nazis. There was only one Gestapo agent for every 2,000 people, whereas in East Germany the Stasi maintained one agent for every 166 people and ran a far larger group of informers. The point made by LeBor and Boyes is that,

“The East Germans could reckon with the strong possibility of an informer at every dinner party. The inhabitants of the Third Reich could, by and large, eat in peace .”34

Further analysis of the relative ineffectiveness of the Gestapo by Mallman and Paul went into far more detail on the lack of manpower and the uncoordinated and inefficient system the Gestapo worked under. What is evident from their work is that it was certainly not a

…thoroughly rationalized mechanism of repression, in which one gear meshed precisely with the other, keeping the entire population under surveillance.35

This inefficiency was particularly apparent in the failure of the Gestapo to destroy the communist underground organization, which was a primary target. While raids against the underground socialist and communist movements were widely played to the press, they never came close to terminating this network.36 Official reports outlined frustrations in internal operations as well as the complete failure to infiltrate revolutionary émigré groups due to the communist counter-intelligence capability.37 What the Gestapo was able to leverage was the willingness of people to voluntary inform of others, “above all women,” who sent their own husbands to concentration camps. The specific case cited in the study was of a working-class woman from Saarbrücken who turned in her husband, a former member of the KPD, for listening to foreign radio broadcasts (and to get rid of him for the sake of her lover).38

The conclusions that can be reached from this information are two-fold. The first is that the Nazis relied on far more than police repression to maintain themselves in power. They had won an enormous amount of support from the population and were able to maintain this apart from their widespread use of torture and imprisonment. Within the home itself, the personal had become political through the agency of millions of women who supported a regime they saw as protecting and shaping the space which defined them as women. A most potent illustration showed the image of white-haired Catholic woman, in repose, with her rosary wrapped around her hands. Around her neck, she wore the “Mother’s Cross” with a swastika instead of a crucifix. Whether this was by her choice or that of her family is irrelevant. The weight of the “habit of millions” that Lenin warned against was now an integral component of German fascism.39

The KPD, despite the mass arrests of their leadership in 1933 and 1934, were able to continually reform and maintain an underground existence. Despite this, they could not strike back against the regime because they did not have the mass support needed, even within their former strongholds. The brave words of their leadership just before the takeover that a triumphant Nazism would lead to a proletarian uprising were false because the KPD never had the capacity to fully engage the masses to overthrow any of the German governments since the collapse of the monarchy.40 An American writer visiting Berlin at this crucial time observed the KPD and described

“…the thin, miserably clad, weak men, women, and children who marched in the biting wind to the Lustgarten to hear their speakers denounce capitalists, could not feel here any immediate threat to the capitalistic system. Theirs was the hatred not of rage, but of despair.”41

In his study of the Independent Social Democratic Party and the Comintern, Robert Wagner began by evoking a Europe on the brink of a revolution that did not happen. In advancing an explanation he challenged all previous scholarship which had ignored

… the failure of the revolutionary movement, except in Russia, to secure really significant support from a particular segment of the working classes, namely women. A more classic case of the historian’s tendency to accept sex as a constant, i.e., to operate in general as if only one sex the male sex exists, would be difficult to find.42

The Kommunistische Partei Deutschland failed to win the support of working-class women in its own revolutionary struggle and in the process managed to provoke the enmity of German women across the class spectrum of Weimar. The disconnect between its revolutionary pronouncements and its actual capabilities was first rooted in its inability to gain the support of all the proletariat (much less the majority of the German people) because of its rejection by women. Even if it had gained this support and launched an uprising, the establishment of a revolutionary regime would have no doubt provoked a civil war. That the party could not win over women and a critical mass of the rest of the population to the necessity of a war between Germans resulted in the Holocaust instead. The KPD failed to overcome the habit of millions and so became their victim.

- V.I. Lenin, “”Left-Wing“ Communism, An Infantile Disorder,” in Selected Works: The Communist International, trans. J. Fineberg vol. 10 (New York: International Publishers, 1938), 84.

- Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty, trans. Arthur Wills and John Petrie (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1973), 125.

- Claudia Koonz, Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family and Nazi Politics (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1988).

- Julia Sneeringer, Wining Women’s Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 6.

- Helen L. Boak, “Women in Weimar Germany: the ‘Frauenfrage’ and the Female Vote,” in Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany (London: Croom & Helm, 1981), 155.

- Ibid, 157.

- Legislation advocated by the KPD included full political equality for women, equal pay, better working conditions protection, recognition of women’s right to work, legal status for legitimate and illegitimate children, abrogation of the abortion laws, and divorce on demand. Ibid, p. 159

- Julia Sneeringer, Winning Women’s Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany, p. 5.

- Donna Harsch, Revenge of the Domestic: Women, the Family, and Communism in the German Democratic Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 21.

- Donna Harsch, Revenge of the Domestic: Women, the Family, and Communism in the German Democratic Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 21.

- Robert F. Wheeler, “German Women and the Communist International: The Case of the Independent Social Democrats,” Central European History 8, no. 2 (June 1975): 133, http://www.jstor.org/stable/454737 (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Ibid, 137.

- See Herman Weber, Die Wanddlung des Wandlung des deutschen Kommunismus, Die Stalinisierung der KPD (Frankfurt a/M, 1969)., and Ben Fowkes, Communism in Germany Under the Weimar Republic (London, 1984) as two of the most prominent examples.

- LaPorte Norman, The German Communist Party in Saxony, 1924-1933 (New York: Peter Lang, 2002)

- See Eve Rosenhaft, “Working-Class Life and working-Class Politics: Communists, Nazis and the State in the Battle for the Streets, Berlin 1928-1932,” in Social Change and Political Development in Weimar Germany, ed. Richard Belles, E. J. Freuchtwanger (London: Croom Helm, 1981), and Chris Bowlby, “Blutmai 1929: Police, Parties and Proletarians in a Berlin Confrontation,” The Historical Journal 29, no. 1 (March 1986), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2639259 (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Richard Bodek, “The Not-so-golden Twenties,” Journal of Social History 30, no. 1 (Autumn 1996): page nr., http://www.jstor.org/stable/3789749 (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Chris Bowlby, “Blutmai 1929: Police, Parties and Proletarians in a Berlin Confrontation,” 151.

- Rosa Luxemburg, “Founding Manifesto of the Communist Party of Germany,” in The Weimar Republic Sourcebook, ed. Anton Kraes, Martin Jay and Edward Dimenbers (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 44.

- Simone Weil, Oppression and Liberty, trans. Arthur Wills and John Petrie (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1973), 28.

- Julia Sneeringer, Wining Women’s Votes: Propaganda and Politics in Weimar Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 15.

- Rosa Luxemburg, “Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle,” Marxists Internet Archive, http://marxists.org/archive/draper/1976/women/4-luxemburg.html (accessed November 12, 2010).

- See Chapters 5, 8 & 13 of George L. Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology : Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (New York, N.Y.: Howard Fertig, 1999) for the essential continuity of Nazism with German conservatism.

- See Appendix A

- The full quote is “ I have always told Rosenberg one doesn’t attack petticoats or cassocks” in response to Rosenberg’s polemics against the Catholic Church. Guenter Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (New York: Mc-Graw Hill, 1964),25.

- David Schoenbaum, Hitler’s Social Revolution: Class and Status in Nazi Germany 1933-1939, Paperback ed. (New York: Anchor Books Doubleday & Company, Inc, 1967), 17-18.

- Claudia Koontz, Mothers in the Fatherland, 5.

- Conan Fischer, Stormtroopers: A Social, Economic and Ideological Analysis, 1929-35 (London: Unwin Hyman, 1983), 118-119.

- Hitler qualified this term describing the left-wing threat to Germany. Harold Callender, “Herr Hitler Replies to Some Fundamental Questions,” New York Times, December 30, 1931. http://www.nytimes.com (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Claudia Koontz, Mothers in the Fatherland, 73.

- Ibid, 87

- Joshi Vadana. Gender and Power in the Third Reich: Female Denouncers and the Gestapo (1933-1945). London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Baldur von Schirach cited in Jill Stephenson, Women in Nazi Germany (New York: Longman, 2001), 163-64.

- Gertrud Scholtz-Klinks was the leader of the Nazi Women’s League. Adam LeBor and Roger Boyes, Seduced By Hitler: The Choices of a Nation and the Ethics of Survival (Naperville: Barnes & Noble/Sourcebooks, 2000), 84.

- Ibid, 3.

- Nazism and German Society, 174.

- Police Raid Reds in German Cities, New York Times, July 30, 1933. http://www.nytimes.com (accessed November 12, 2010).

- Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Gerhard Paul, “Omniscient, Omnipotent, Omnipresent? Gestapo, society, and resistance,” in Nazism and German Society 1933-1945, ed. David F. Crew (London: Routledge, 1994), 182.

- Ibid., 180.

- see Appendix B

- William C. White, “Flashes of Red in the German Picture,” New York Times, April 3, 1932. http://www.nytimes.com (accessed Nov 12, 2010).

- Calvin B. Hoover, German Enters the Third Reich, new York: Macmillan, 1933. Pg 48

- Robert F. Wheeler, “German Women and the Communist International: The Case of the Independent Social Democrats,” Central European History 8, no. 2 (June 1975): 113.

38 Replies to “Frauen und die rote Fahne: Gender and the Destruction of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschland”

Comments are closed.