The history of early American Marxism is one of a failed colorblind politics that was incapable of organizing the proletariat in post-Reconstruction United States, argues Donald Parkinson.

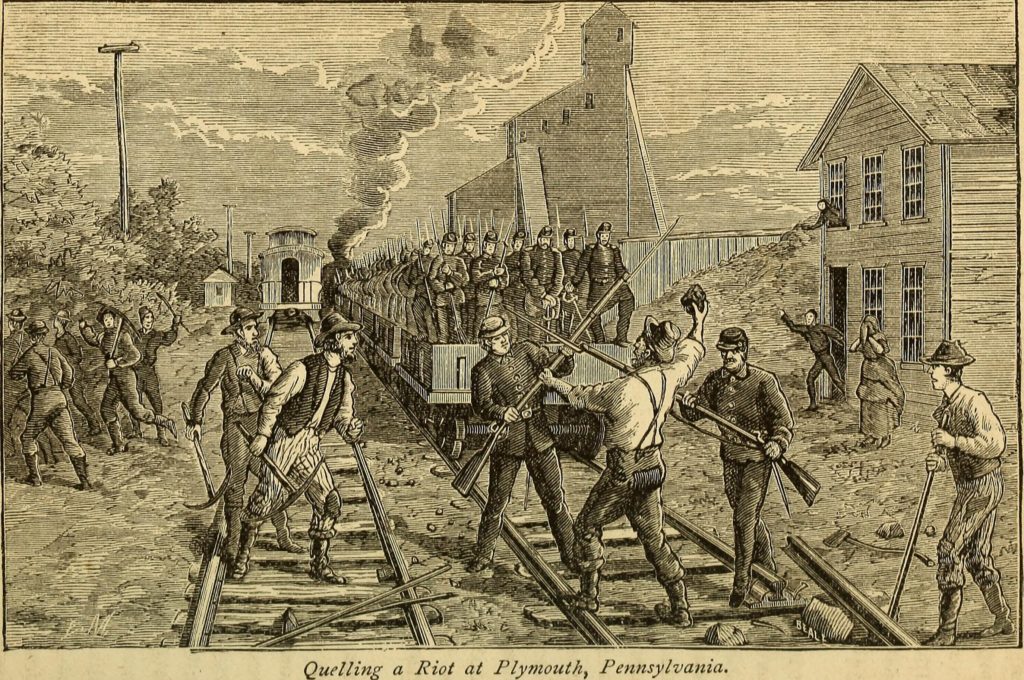

In July of 1877, working-class revolt hit the United States. Beginning in Martinsburg West Virginia, rail-workers went on strike against a wage cut imposed by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The strike would spread to a nation-wide phenomenon, spreading to West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio and then Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, and San Francisco. One hundred thousand workers were on strike with federal troops being called in to suppress a strike for the first time since Andrew Jackson’s presidency. It St. Louis the strike would spread to workers of all industries, shutting down the city in a general strike. On a scale unprecedented in the United States workers were mobilizing through militant action to fight for their interests.1

Newspaper accounts would attempt to blame the rising of the strike on a single entity: the Workingmen’s Party of the United States, who were portrayed in one newspaper being akin to “Robespierre and his brace of Fellow Conspirators” who “sit in darkness and plot against the life of the nation.”2 Historical accounts published shortly after the event would also make similar claims, Allan Pinkerton, for example, claiming the mass strike was a “direct result” of agitation and organization on the part of the Workingmen’s Party.3 While the press was not unanimously against the cause of the strikers, those who didn’t sympathize could only see communist conspirators behind the scenes pulling the strings. While it is true that the Workingmen’s Party had members who were involved in the strike to varying degrees in certain localities, the actual uprising itself was a result of defensive action on the part of workers defending their livelihoods.

Rather than capable of inspiring a mass upheaval on the scale of what was seen in July 1877, the Workingmen’s Party of the United States was more a sect than a mass party. The party was formed a year prior to the “Great Upheaval” of 1877 in an 1876 convention which united various socialist organizations and trade unions that were followers of either Karl Marx or Ferdinand Lasalle. At this point, the organization likely had less than three thousand members, hardly a mass organization that could single-handedly inspire a labor uprising on the national scale.4 However, given the opportunity for agitation and intervention in class struggle presented by the “Great Upheaval” former Socialist Labor Party (the organization the Workingmen’s Party would transform into in December 1877) member Girard Perry would claim in his history on the organization that “it would have been hard to choose a better year than 1876 to launch a revolutionary socialist party in America”.5

While membership in the party would rise to around 7000 members in 1878, this rising level of membership would not be maintained.6 Rather than developing into a mass party like the German Social-Democrats, the Socialist Labor Party would fail to maintain steady growth and develop itself into a real force in the labor movement. As the “Great Upheaval” had shown, there was no lack of a labor movement willing to fight for economic demands in the United States. Yet socialists as an organized force, such as the SLP, were unable to make any real headway into the working class as a whole, failing to merge socialism as a political ideology with the workers’ movement at large. Rather than growing into a mass party the SLP would split and fragment, endemic of the situation which led Werner Sombart to write his essay Why Is There No Socialism in the United States?.

This article will engage with the political culture and ideology of the WPUS/SLP, and analyze the factors in the failure of these parties to ultimately rise beyond being mere sects to become mass workers parties. By doing this I will argue that the SLP’s failure to comprehend the nature of racial divisions in the working class, and the oppression faced by black workers, left it as a force incapable of resonating with the black working class at large and presenting labor as a force that carries with it the emancipation of all humanity. Hindered by an overly economistic reading of Marxist ideology, the WPUS/SLP assumed that economic pressures would lead to working-class unity and militancy. This blindspot regarding race would leave the party incapable of acting as an effective force given the conditions of the United States. When looking at debates about race and its relation to the socialist project today, we cannot get lost in theoretical debates about the ontology of identity, rather we must look at the actual history of Marxists in the United States and how they related to the actual black freedom struggle of the day. The lessons to be drawn for modern socialists should be clear for those who take an honest look at history. To begin this investigation, we will begin with a look at the historiography of the WPUS/SLP and how historians have discussed their racial politics.

Delving into the History

The history of the Workingmen’s Party of the United States and Socialist Labor Party is mostly scattered throughout larger volumes that cover the history of early US socialism. Only one full volume dedicated solely to the Socialist Labor Party exists, Frank Girard and Ben Perry’s The Socialist Labor Party, 1876-1991: A Short History, which is in fact written by ex-members of the party in its later years and only around one hundred pages in length. Girard and Perry’s Short History also only spends around 25 pages on the group in its earlier years (1876-1899) when it stood as the only party associated with Marxist thought in the USA. Due to being written by former members who are admittedly not trained historians, the work also lacks a critical perspective toward the party. Nothing is said about the attitude of the party towards the black working class, with the general failure of the party to gain a mass following being blamed on the SLP’s “alleged association – carefully fostered by the capitalist press – with the Paris Commune and the “crazy” element among the Bakuninists.”7

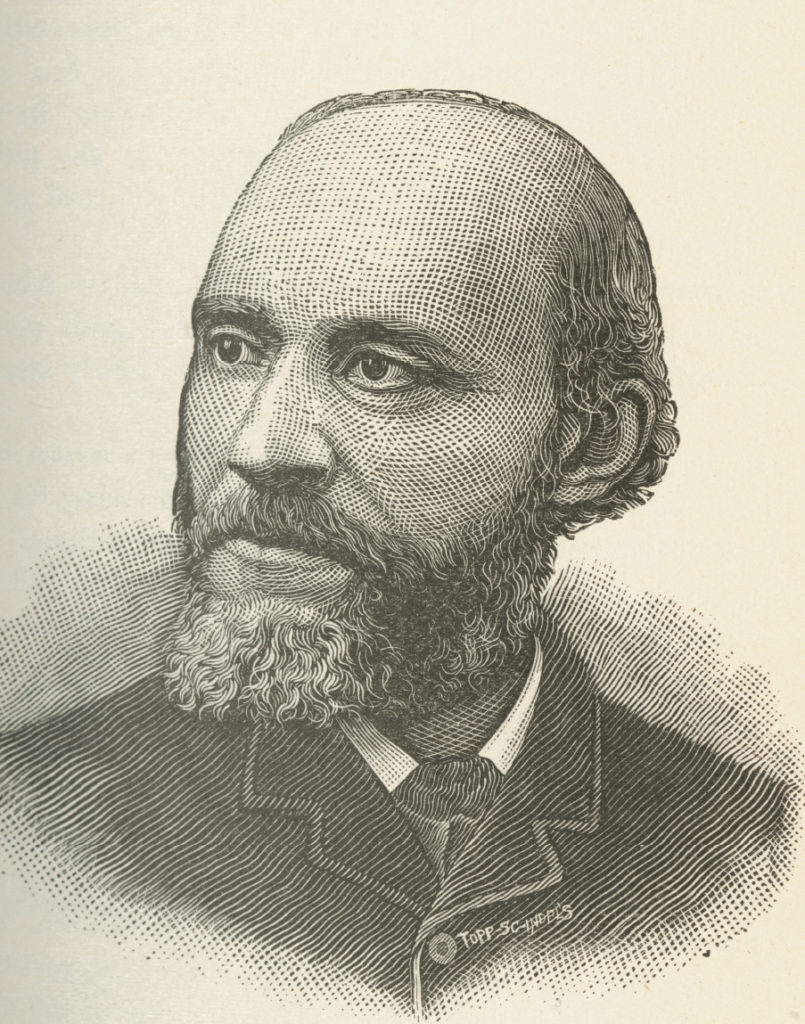

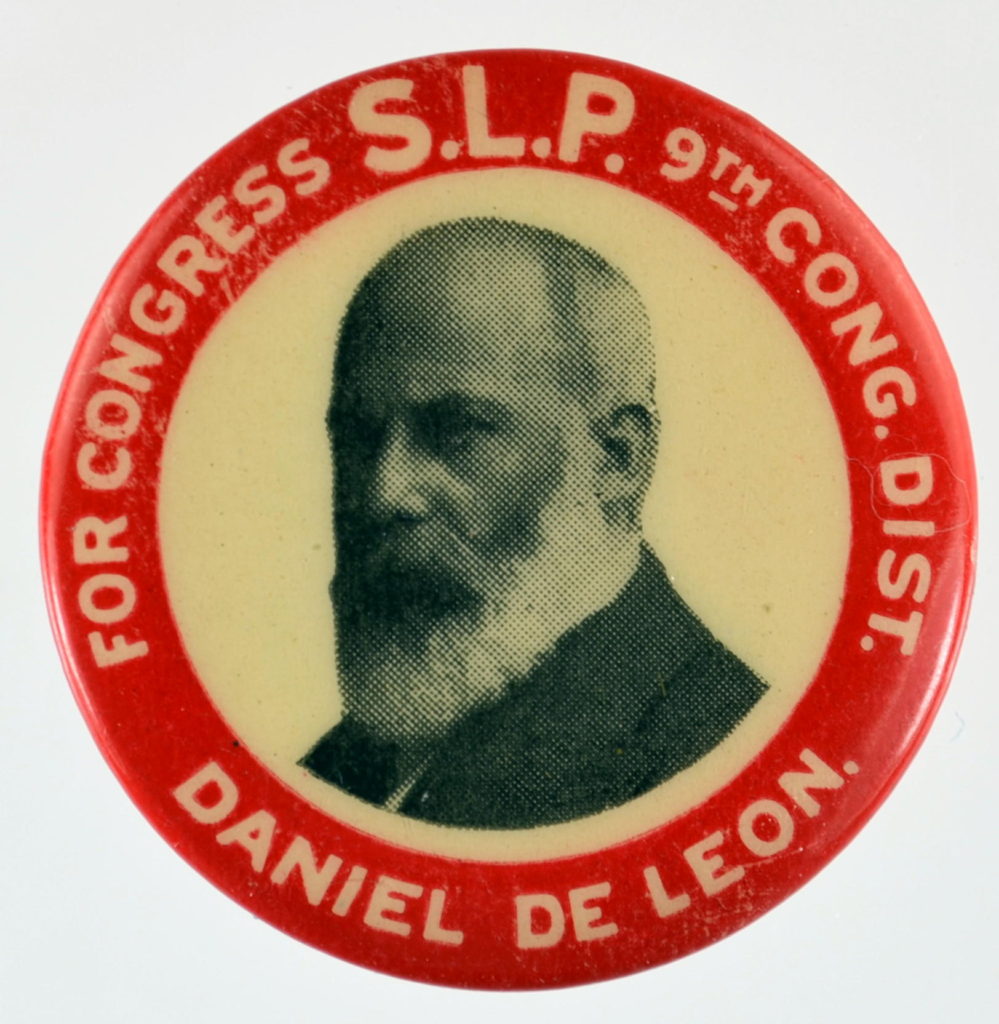

Morris Hillquit’s History of Socialism in the United States, first published in 1903, has extensive information on the early period of the WPUS and SLP and the socialist movement in the United States before it. Hillquit himself was a member of the Socialist Labor Party, joining in 1887. His disagreements with Daniel DeLeon, who had consolidated leadership in the party in the 1890s, led him to leave with a dissident faction, merging with the Victor Berger and Eugene V. Debs’ Chicago-based Social Democratic Party to form the Socialist Party of America in 1901. Hillquit’s historical perspectives are therefore heavily informed by this political context, with his book just as much an expression of the ‘centrist’ Marxist ideology present in US Socialism at the time as it is a proper history. This is evident in his highly negative attitude towards the anarchists who would split from the party in 1880, forming a Revolutionary Socialist Labor Party in 1880.8 It’s also evident in his attitude towards the SLP’s policies on trade unions after leadership was transferred to DeLeon, which was to leave the existing craft unions and form a “Socialist Trade and Labor Alliance” to replace them.9 As a result, Hillquits’ book, while containing much useful information, is heavily informed by the political polemics he was embroiled in.

Regarding the topic of race, Hillquit reveals little about how the SLP approached these issues, not even mentioning the contributions of black socialists like Peter H. Clark. In one section of History Hillquit discusses the reasons why socialism was slow to pick up in the United States, his reasoning completely oblivious to the role of racial divisions in weakening working class consciousness. This is evident by his claim that “In the United States, however, the working men enjoyed full political equality at all times, and thus had one less motive to organize politically on a class basis.”10 This was in contrast to the workers in European countries, where workers movements could unite around fighting for democratic rights against aristocratic regimes. By claiming that in the United States political equality is the norm, Hillquit reveals complete blindness to the subjugation of millions of black workers and their exclusion from having full political rights. Rather than a country where no democratic struggles existed to bring the working into politics beyond trade unionism, the black democratic struggle for political rights was a vital part of US political life that goes unnoticed for Hillquit.

Due to the level of information, Hillquit’s book is a key source for basic history regarding the Workingmen’s Party and SLP. However, it is far from the only historical work to touch on its history at considerable length. In the 1960s and 70s, a rising interest in the history of Socialism and Marxism in the US would inspire historians to take a closer look at the pre-Socialist Party and CPUSA era of US radicalism. One of these works would be David Herreshoff’s The Origins of American Marxism, which contains a considerable amount of information on the WPUS/SLP. Herreshoff attempts to trace out an American radical tradition that would culminate in the Communist Party, beginning with the transcendentalists like Emerson, anti-abolitionist labor radicals like Brownson and Kriege, and then the German-Americans like Sorge and Weydemeyer. This narrative isn’t exactly convincing; Emerson was an individualist who was far from a materialist in his ideology, with Brownson and Kriege’s views, that abolition is less important than the labor radicalism of white Americans, putting them at odds with the abolitionist German-American immigrants who brought Marxist ideology to the US, such as Joseph Weydemeyer who would serve as a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War.

Regardless of these confusions, Herreshoff’s work does show itself capable of recognizing the issues of race as an obstacle to socialist politics gaining headway in the United States. He touches on this in the intro, claiming:

“Egalitarian movements, to their own undoing, tend to be self-centered. Seldom in good rapport with one another, they frequently begrudge one another’s right to exist. The labor radical who anti-Negro, the abolitionist or Negro leader who is pro-capitalist, the feminist who is for the open shop, and the agrarian who is against women’s rights are recurring figures in American history. The movements therefore find it difficult to make alliances among themselves, and much of the momentum of social discontent is dissipated by their rivalries.”11

Herreshoff then goes on to argue that the tendency for labor movements to become concerned with broader social issues beyond the immediate economic sphere is “implicit”, that a movement towards concerns with broader social issues is a key part in what defines Marxian “class consciousness”. Yet in the United States, this leap was never made, with labor merely acting as a pressure group within society to meet the sectoral economic interests of workers.

With this perspective, Herreshoff is able to provide some level of insight on how the SLP viewed the question of race and suggests it is linked to their failure to develop as a party. While not fully developing this idea he does discuss the impact of an insufficient understanding and platform on race being a weakness of the party. He claims that it was not until after WWI that Marxists in the US recognized that the victory of the Union in the Civil War and the abolition of slavery did not fully realize political equality and freedom from racist oppression for blacks. He raises prominent SLP member Daniel DeLeon’s reaction to attacks on black suffrage as an example of the poverty of US Marxism’s views on race, showing how he believed “it was a waste of time to explore the differences between whites and blacks.”12 He also notes that DeLeon saw far more potential in the struggles for women’s equality than the black struggle.13

Another work that contains useful information on the WPUS/SLP is Oakley C. Johnson’s Marxism In United States History Before the Russian Revolution (1876 – 1917), published in 1974. The work is published under the tutelage of the American Institute for Marxist Studies, which aims to “encourage Marxist and radical scholarship in the United States” while aiming to “avoid dogmatic and sectarian thinking”. 14 Johnson’s book is useful not only for its information on the Workingmen’s Party and SLP but also because it compartmentalizes the history of early US Marxism according to specific social issues and spheres of life. This means that are not only chapters on the role of Marxism in reform movements, the battle for women’s suffrage and the black freedom struggle but also the role of Marxism in prose, poetry, political cartoons, and youth organization. This provides a look at the history behind the WPUS/SLP that isn’t limited to the questions of political congresses and internal factional debates which in turn gives the reader a better view on what kind culture and ideology existed within the organization. By examining these topics separately Johnson aims to make the argument that even before the impact of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 “Marxism, although a minor factor in our history, was nonetheless a significant one.”15 He also aims to show that Marxists, while not always ideal, were nonetheless on the side of progress with respect to all social issues.

The chapter Marxism and the Negro People’s Freedom Struggle from Johnson’s book is of particular interest to this project. Johnson, keeping with his theme of Marxism being at the vanguard of progressive social ideals, generally emphasizes the aspects in which the SLP was progressive regarding the black freedom struggle. His arguments for this do not always hold up perfectly, however. One example is the claim that Frederick Douglas was influenced by the SLP, basing this claim off similarities in political rhetoric while admitting there is no evidence Douglas ever actually engaged with or even knew of the SLP.16 Johnson also points out the presence of prominent members of the SLP who were black such as Peter H. Clark and Frank J. Ferrel. While the prominence of black members like Clark and Ferrel in the party does show the organization wasn’t an explicitly racist entity that excluded black members or purposely held them in subordinate positions in the party, it isn’t necessarily evidence that the party was able to strike a chord with the masses of black workers who had been mobilized in the struggles of Reconstruction.

According to Johnson’s narrative, the party didn’t fail to properly address questions of racial oppression until Daniel DeLeon would take leadership of the party.17 With DeLeon the party would move towards a more “doctrinaire” and class reductionist approach. He quotes SLP secretary Arnold Peterson, summarizing the views of DeLeon: “there was no such thing as a race or ‘Negro question’…that there was only a social, a labor question, and no racial or religious question so far as the Socialist and labor movement were concerned.” While Johnson does not doubt that DeLeon rejected the notion that blacks were inferior, he does believe the claim that DeLeon failed to recognize the necessity for socialists to actively campaign and fight for the rights and dignity of African-Americans. By denying there was such thing as a “negro question”, the SLP would be incapable of fighting against the racial divisions in the working class. The Socialist Party, which developed as a split from the SLP after the rise of DeLeon’s leadership, is portrayed as making a genuine move towards being capable of dealing with the special oppression of racism. Johnson recognizes this in a resolution passed in its 1901 founding convention that would state that the black working class:

“because of their long training in slavery and but recent emancipation therefrom, occupy a peculiar position in the working class….therefore, we, the American Socialist Party, invite the Negro to membership and fellowship with us in the world movement for economic emancipation by which equal liberty and opportunity shall be secured to every man, and fraternity become the order of the world.”18

This is recognized as an improvement from the SLP’s program under DeLeon’s position but still not sufficient, as it was merely a call for sympathy and unity rather than for taking action against the specific actions that black Americans faced.

The problem with Johnson’s narrative regarding the SLP is that he does not sufficiently establish that the SLP pre-DeLeon had a coherent platform regarding the black struggle. The narrative provided essentially shifts all blame to DeLeon and acts as if the party before his leadership had no deficiencies regarding the question of race. Johnson provides plenty of direct evidence that the SLP after DeLeon’s leadership had insufficient understanding of racism in the US, yet provides a very weak argument that it’s program beforehand was much better.

Paul Buhle’s Marxism in the United States places the SLP in the tradition of “19th-century immigrant socialism”, dividing it into two phases: the period from Reconstruction to the “Great Upheaval” of 1877 to the period following the “Great Upheaval” to 1890s where the SLP struggled to maintain relevance. For Buhle a primary issue in the history of US socialism is the contradiction between the status of many of its adherents as immigrants and “foreigners” and the need for the movement to “Americanize” to conform to the national conditions of the US. Subscribing to a doctrinaire understanding of Marxism, US socialists were unable to see beyond class issues in order to make alliances with reform movements native to the US. Buhle sees the period prior to the formation of the SLP, where various local groups affiliated to the First International, as being more successful due to its “heterogeneity”.19 For Buhle the main challenge facing Marxist socialists in the US was an inability to properly access the specific conditions of the US and then reflect such as assessment in their political practice.

Another factor at play for Buhle is the nature of US trade unionism, which factors into how he explains the failure of US Marxists to incorporate black workers into their politics. Marxists held a “presumption that trade unions represented the general interest of the working class”. This presumption meant that Marxists would carry a strategic vision that would exclude workers who were largely excluded from unions: women workers and black workers. As a result “The historical experience of Black activity in the Civil War and Radical Reconstruction left no trace in the Marxist sensibility.”20 This would also apply for other ethnic groups such as the Irish who were unable to be “disciplined like trade unionists” due to factors such as unemployment. This led Marxists to view black radicals as “lumpen proletarians” who were not part of the proper proletariat. As a result, US Marxists, many German-American, would “constitute an extraordinarily well educated and disciplined band, able to quote chapter and verse from Capital or to direct a trade-union struggle” but ultimately incapable of striking a chord in the most oppressed and exploited members of the working class.21

Buhle’s narrative is essentially that of foreigners carrying a foreign ideology, incapable of developing their politics to meet the specific conditions of the US. Racial divisions in the US working class were just one of these divisions, with Buhle also mentioning the inability of US Marxists to adequately address issues of women’s oppression and suffrage. To paraphrase him, Socialist Labor Party members in 1877 would be disappointed by their failure to more effectively intervene in the nation-wide mass strikes that erupted in July; in the 1890s the SLP would yearn for the level of influence they had in 1877.22 The 1890s SLP is presented as a party in crisis, essentially meeting its fate of being confined to marginality. He presents DeLeon as essentially entering a party “ripe for takeover” in 1890 and providing it with a level of ideological consistency and direction that it did not previously have.23 However, like Johnson in his Marxism in United States History before the Russian Revolution 1876-1917, he does see DeLeon as having an overly narrow view of class:

“Even if the economic and political crisis of American society had been total, DeLeon failed to grasp the lineaments of a credible alternative. He treated the multiplicity of working-class internal divisions, the complexity of social unrest among wide classes of Americans, by leveling Marxist theory down to an impossibly narrow concept of class. He saw no class worth considering but the abstract working class.”24

Where Buhle’s interpretation differs from Johnson is in his rejection of a narrative that sees the Socialist Labor Party as being able to adequately address the race question and strike a chord amongst black workers before DeLeon’s rise to leadership in the 1890s. For Buhle the problem is there from the beginning days of the party. DeLeon’s mistakes were not a divergence from the party’s prior path but rather “unwittingly caricatured the gravest errors German-American Socialists had made toward American social life.”25

Philip S. Foner would contribute to the historiography on the Socialist Labor Party by covering its early predecessor the Workingmen’s Party of the United States in his book The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. Foner focuses on the role of the party during the nation-wide mass strikes that hit the United States in July of 1877 while also giving an overview of the party’s origins and general political outlook. Foner portrays the Workingmen’s Party as mostly playing a role of moderation, urging against violent mobs damaging property and trying to channel discontent into clearer political struggles.

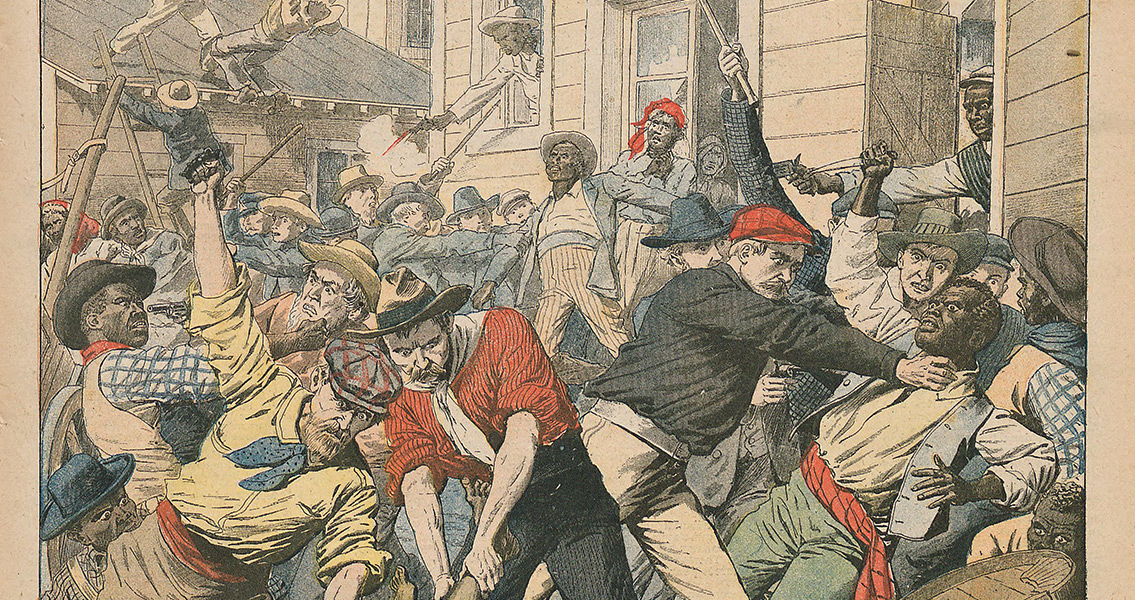

Foner touches on the attitude of the Workingmen’s Party toward black Americans in two notable parts of his book. Regarding the unity conference of the party and the programmatic statements it would reproduce, he notes that neither the party’s Declaration of Principles or eleven demands gave any attention to the struggle of black Americans.26 He also discusses the issue of racism and the WPUS when discussing their role in the St. Louis General Strike. During the Great Upheaval, St. Louis had essentially been shut down by strikers with an Executive Committee run mostly by WPUS members elected to manage the strike. Foner portrays the Executive Committee as largely vacillating to the forces of law and order, issuing a statement to the mayor that it would assist in “maintaining order and protecting property” and that they were “determined to have no large processions.”27

This decision to forestall what was essentially a mass working class insurrection and call for a return to order is partially explained by Foner as related to racism (amongst other factors such as the influence of Lasalleanism). He notes that the Workingmen’s Party in St. Louis made little effort to recruit black workers and that unions in the city also made little effort to organize them. Black workers had played an active role in the St. Louis strike, with many white workers demonstrating a willingness to unify with them in common struggle. Foner quotes Albert Currlin, a WPUS leader who was a member of the Executive Committee deriding black participants in the strike with racial epithets while claiming they were refused membership to the party.28 The quote provided by Currlin is used by Foner to demonstrate that one reason the WPUS led Executive Committee would shut down mass meetings and large scale processions were out of a fear of mass black participation, demonstrating how racism actively held back the party in keeping apace with the radicalism of workers. While other works mentioned beforehand do not touch on the presence of white supremacist attitudes within the party and instead claim that the parties ideology was merely insufficient regarding race, Foner provides damning evidence that the internal culture of the WPUS (which would later become the Socialist Labor Party) did contain direct racism in certain locals which was present within the parties public statements. This racial conflict within the strike was a product of a greater division within the working class based on race, yet the WPUS did not act against the chauvinism of the masses by truly leading the working class to fight for emancipation but rather went with the flow. To get a more in-depth understanding of the ideology of the WPUS an analysis we will have to take a look at some of the actual speeches and documents produced from this time.

Early US Socialists in their own words

By looking at actual recorded discourse from the time, it is possible to get a sense of how accurate various historical understanding of early US Marxism. While the picture revealed by looking at these programs, speeches and essays are more complex than one of vulgar and chauvinistic white Marxism, there can be no doubt that the WPUS/SLP suffered from what Noel Ignatiev would call a “White blindspot”. To begin, we will look at the party programs of these organizations and their development. The Platform of the Social Democratic Workingmen’s Party of North America was published in the party newspaper The Socialist on June 24, 1876. It is divided into three parts, part A summarizing the final goal of the party in one sentence (“to establish a free state founded upon labor”), part B listing basic principles that all party members are expected to uphold and part C listening basic demands of the party.

The basic principles of the party call for the “abolishment of the present political and social conditions” and “sympathy for workingmen of all countries, who strive to attain the same object” but say nothing about rejecting racism in the specific. Likewise, the demands listed say nothing about the rights of blacks in particular or the abolition of laws that promote racial discrimination. While addressing the rights of women by calling for “Regulation of female labor in occupations detrimental to health of morality” and “Equalization of women’s wages with those of men” it is strictly within the framework of labor that these issues are addressed. The program does demand suffrage for “inhabitants over 20 years of age” but does not specify that suffrage should apply for African-Americans, which while formally granted by the 15th Amendment was constantly under attack by reactionary politicians and vigilantes. Overall the demands listed are strictly related to either the question of political democracy in the state or are part of the labor question.29

In December 1877 the Workingmen’s Party would change its name to the Socialist Labor Party (initially Socialistic Labor Party) and issue an updated platform. This updated platform did include an expanded resolution on rights of women (claiming “the emancipation of women will be accomplished with the emancipation of men, and the so-called women’s rights question will be solved with the labor question”) but added nothing regarding the issues or racism or the rights of black Americans.30 The way that the resolution on women’s rights is phrased reveals an unwillingness to see forms of oppression taking on an element that is not completely subsumed to economic class. This shows how an ignoring of race can be tied to a general problem of “economism” where all issues not related to the economic conditions of waged labor are ignored or reduced to a mere aspect of waged labor. Economism glorifies the bread and butter struggles of union workers and their militancy while degrading the importance of democratic struggles against colonialism, racism, patriarchy and general oppression.

By overviewing the different platforms of the SLP throughout its history one finds that the mere mention of race is not added to the parties National Platform until 1956, long after the party had been replaced by the Communist Party USA as the primary organization of Marxists in the United States.31 Even then, the platform merely mentions that socialism is the sole answer to the problems of race prejudice, saying nothing about the need to combat these prejudices within the working class in order to reach the class unity needed for socialism.

Taking a look at speeches and writings by members of the Workingmen’s Party and Socialist Labor Party can also provide insight into how the organization dealt with racism and the black freedom struggle. Peter H. Clark’s speech Socialism: The Remedy for the Evils of Society is according to Philip Foner “probably the first widely publicized proposal for socialism by a Black American” and for that reason alone is important in the study of how early US Socialists dealt with issues of race.32 Clark was originally a member of the Republican Party and part of its most radical wing but would abandon the party at the end of Reconstruction to become a socialist and join the Workingmen’s Party of the United States. In 1878 he would run for Congress as a member of Socialist Labor Party in an unsuccessful campaign. Clark’s speech was delivered during in Cincinnati during the Great Upheaval of 1877 to a mass meeting that was called by the Workingmen’s Party.

Clarks speech begins by quoting a man who may seem like an unlikely choice for a socialist to some: Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln is quoted as saying “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.” This quote reveals an almost religious humanistic element to the socialism that Peter H. Clark would espouse, showing that his ideology was not completely within the bounds of orthodox Marxism. Throughout his speech Clark proclaims he is on the side of the strikers but condemns violence, expressing a universalist humanism that seems to have more in common with the “love thy neighbor” ethos of Christianity rather than the class struggle world-view of Karl Marx. Clark appeals to more than just the economic interests of workers but to general notions of justice and humanity. This problematizes the notion that the WPUS/SLP was homogeneously stuck in a mechanistic and economistic worldview from its inception. With this in mind, Clark does use many arguments derived from Marxist materialism, citing the inevitability of economic crisis and increased the concentration of wealth inherent to capitalism.33

More importantly, the fact that Clark begins with a quote by Lincoln reveals a perceived connection between the emancipation struggles of the Civil War and Reconstruction for the freedom of black Americans from the yoke of slavery, with the struggle of labor against the wage system. The battle for political equality for black Americans in the struggle against the plantation aristocracy of the South would bring questions of economic equality to the forefront in civil society with a rise of labor activism, most notably in the first campaigns for an Eight Hour Day. The use of Lincoln, an icon of Radical Republicanism, reveals a perceived connection between the struggle of waged labor and the struggle of black freedom. This connection is not explicitly but rather implicitly made.

While making a connection between the struggle of the strikers in the 1877 Upheaval and the freedom struggle of Emancipation and Reconstruction, Clark only makes one explicit mention of race in his speech. This is in the context of discussing the pitfalls of the democratic system. When discussing the electoral system Clark sees an “alarming spread of ignorance and poverty” which creates “an ignorant rabble who have no political principle except to vote for the men who pay the most on election day and promise to make the dividend on public stealing.” He adds that for black Americans the crime of voting for corrupt bourgeois politicians is not their fault as they are “scarcely ten years from slavery” and not “the chief sinner in this respect”. Beyond this Clark mostly ignores issues of race, but does recognize that the impact of slavery on black workers adds a specific element to their impression. While Clark’s attitude is ultimately paternalistic toward the ability of freed blacks to govern, it is nonetheless an acknowledgment of the special oppression black Americans face. This isn’t found in any of the other primary source documents analyzed.

Another important voice of the Workingmen’s Party and Socialist Labor Party was the German-American Friedrich Sorge. During the Civil War Sorge was an active anti-slavery agitator and after the war become a major proponent of Karl Marx’s theories in the United States. He established the New York section of the First International and would serve as the general secretary of its worldwide organization from 1872-74 before the International would fall apart due to the split between followers of Marx and Bakunin. In 1876-87 he was a founding member of the Workingmen’s Party and the Socialist Labor Party while in close correspondence with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. All of this biographical information points to Sorge as being a key ideological figure in the early SLP and US socialism in general.34

Due to the prominence of Sorge as a key ideologue in this Socialist Labor Party, his pamphlet Socialism and the Worker is indispensable for grasping what kind of ideology was prominent in its leadership. Socialism and the Worker is largely a response to arguments against socialism, defending it against accusations such as socialists wanting to confiscate all property and redivide it. By responding to common arguments against socialism, Sorge attempts to better clarify what it actually stands for and why it is in the interests of all workers.35

Sorge doesn’t directly touch on the issue of race except in discussing slavery. He claims that “The development of mankind to greater perfection was and never will be arrested by the prevailing laws concerning property. For instance, it was not arrested, when humanity demanded the abolition of slavery, by the pretended divine right of slave-owners.” As with Peter H., Clarke this shows that Sorge recognizes some form of link between the struggles of Radical Republicans and Abolitionists against slavery and the struggle of labor against capitalism. He then adds on that “At the bottom of our institutions there is a remnant of slavery; as soon as capital shall cease to govern, wage-labor and the rest of slavery will be abolished.” Whether this means that there is still a remnant of institutional racism due to the impact of slavery or that wage labor is a form of slavery is not exactly clear. If he means the former, it could be argued that he is unaware of the consequences of this impact, as Sorge will also say in his speech that “the interests of all workers are the same”. While one could argue that this is true in the long run and that socialism would benefit all workers regardless of skin color, one could also see it as ignoring the reality of the working class existing as a divided entity due to the ideological grip of white supremacy over the working class whites. If the interests of all workers in the United States were indeed the same, then why have so many white workers chosen solidarity with bosses of the same skin color over solidarity with their fellow black workers and other ethnic minorities? This understanding ultimately reveals a blind spot and “colorblindness” in the ideology of Sorge who would be an influential voice in the WPUS and SLP at large.

Another key ideologue of the Socialist Labor Party would be Daniel DeLeon, who in the course of the 1890s would take a party in crisis and establish himself as its leader. DeLeon is a polarizing figure in the history of US Socialism with the aforementioned Oakley C. Johnson blaming him for implanting a dogmatic and inflexible brand of Marxism into the Socialist Labor Party.36 Paul Buhle portrays DeLeon as providing much needed intellectual leadership to the party yet also continuing previous errors of US socialism.37 Under DeLeon’s leade,rship the party would publish The People, a paper designed to bring Marxist analysis of current events and political issues to the masses. The following sources that will analyzed come from this paper.

Restiveness Among Colored Workingmen begins by criticizing a New York newspaper published by African Americans titled The Age which is critical of the Republican Party for its discriminatory policies. In this particular, case it is pointing out the prominence of Southern white men in the McKinley administration, asking the question “Are we (the colored people) in politics?”. DeLeon essentially chastises the writer for suggesting that racial discrimination is the cause of black exclusion from politics, saying that “the neglect of which they complain is in no way attributable to their color, but is closely akin to the treatment which the Republican party bestows on the WORKING CLASS.” For DeLeon these complaints of racial discrimination are a false complaint – the issue here is not race but class, and to bring a racial dimension into the equation is to distract from the key issue of waged labor.38

DeLeon would also claim that black workers in the US will eventually emerge from their “Deceptions” and join the white working class in a common unified struggle. Black workers are essentially tied to the Republican Party due to its role in giving them recognition during Reconstruction, but with the rise of industrial capitalists dominating the party a break is inevitable and black workers will realize that they are not victims of racial discrimination but rather the exploitation of waged labor. In this conception, the rise of a working-class consciousness is almost inevitable. The illusions that keep workers tied to capitalist parties will be shed and workers will unite despite racial difference due to their common class position. For DeLeon a conscious effort to struggle against radicalized divisions within the working class is not necessary. Economic necessity alone will suffice. Again we see the ideology of economism.

Race Riots, another DeLeon piece for his daily edition of The People, was published in 1900. The article discusses a race riot in New Orleans and also shows an incapacity to even recognize the existence of a “race question”. DeLeon doesn’t provide any real details on the riot itself other than describing a “slaughter of Negroes in New Orleans by the mob”. Skipping any journalistic intrigue, he cuts straight to the ideological point. The riot isn’t a “War…between black and white” but rather a “war between workingmen, and the prize they battle for is a “job””. He even goes as far as to deny that the riot has anything to do with “Racial hate” whatsoever. He instead condemns the “ignorant workmen…both black and white” for not uniting to fight against the capitalist system. The only solution to race riots is socialism, and while DeLeon is clear that workers of all color must unite to end it he provides no insight in how to do this.39

A consistent theme in primary sources of the Workingmen’s Party and Socialist Labor Party is an inability to recognize that black workers faced a form of extra-economic oppression due their skin color which could not simply be reduced to their relationship to the means of production. The closest any of the aforementioned writers come to moving beyond this viewpoint is in the speech of Peter H. Clark, who was himself black and previously involved in the struggle for abolition and political rights during Reconstruction. The Socialist Labor Party’s unwillingness to even recognize the existence of a “Race question” in their platform until long after their relevance shows an extreme blind spot to the conditions they faced organizing a working class in a nation heavily divided by race relations. Early US Marxists were incapable of striking a chord in the masses of black workers with their colorblind politics that would have appeared blind to the actual social forces that were at play.

Conclusion

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP) and its predecessor the Workingmen’s Party of the United States (WPUS) were the first attempts at forming a mass scale working class party with an explicitly socialist orientation in the United States. The SLP would give rise to both the Socialist Party of the United States as well as the Comintern affiliated Communist Party of the United States and therefore acted as a key point of origin for the most well-known organizations of US radicalism. It was also the first attempt to build an organization on a national scale that explicitly fought for a socialist future, and while not explicitly Marxist (its ideology more a fusion of Marx and Lasalle), it represented an attempt to apply the general thesis of Marx’s doctrine of class struggle in the United States. Despite serving as a key starting point in the development of US radicalism, the SLP would only come to a mass following for brief periods of time and would fracture into a multitude of splits, never developing into a mass workers party with the consistency and influence of the German SPD or even the Italian PSI.

The failure of the SLP to develop into a mass workers party raises important historical questions, questions most famously raised by German Sociologist Werner Sombart in his book Why is there no Socialism in the United States?. Noting the scale and size of the German Social-Democratic movement, Sombart would respond to this development by asking why such a movement didn’t exist in the United States. Sombart would answer this question by looking towards the two-party monopoly on politics, the civic integration of American workers, greater opportunities for social mobility and the existence of an open frontier which provided supposed opportunities for landed independence. These arguments, while they may have their merit, don’t take into account the actual political culture and strategic approaches that socialists in the United States developed in order to merge their ideology with the working class. Sombart instead focuses on the “embourgeoisement” of American workers due to external economic factors.40

A more developed study of the SLP and early US socialism before the rise of the SPUSA and CPUSA is of importance not only because of the lack of literature written on this specific topic by people who weren’t political partisans of the era. It is important for answering the question raised by Sombart without merely blaming external factors. If one rejects vulgar economic determinism then the development of a mass socialist consciousness amongst the working class is not a “natural” outgrowth of economic conditions but is related to the efforts of conscious socialists to merge their ideology and politics with the working class. Therefore a closer look at the actual political culture, ideology, strategic orientation and tactical approaches of the WPUS/SLP can help develop an understanding of why a mass scale socialist party wasn’t able to develop in the United States.

Taking a closer look at the ideology and political culture of the WPUS/SLP reveals that the organization was informed by a form of “colorblind” Marxism that was incapable of dealing with the realities of racial divisions in the class structure of the United States. While more progressive on issues of race than other political parties in the United States, the WPUS/SLP ultimately failed to make a connection with the black working class, a grouping in society that had shown itself to have enormous revolutionary potential in the period of Reconstruction. While standing for class unity and recognizing the need for inter-racial organization, the WPUS/SLP ideology under closer scrutiny reveals an inability to recognize that black workers in the United States faced a form of oppression that was unique to their racial status, with white supremacy acting as a key linchpin in the class structure of US capitalism. This “color-blind” socialism was ultimately incapable of resonating with black workers. It also falsely expected the proletariat to organically unite under economic pressures as it grew as a class, responding to immiseration and crisis in an almost automatic way. This was a vision that was incapable of taking into account the role of white supremacy in dividing the US working class to develop a strategy that could effectively win the most oppressed sections of the proletariat to socialist politics.

When organizing a mass proletarian movement today, we cannot make the same mistake as the WPUS/SLP and assert a narrow focus on the economic struggle at the disdain for democratic struggles, such as the fight against racism. Black Americans, essentially an internal colony, were fighting for a sort of “national liberation” struggle for democratic rights that only formally was won with the passing of the Civil Rights amendments. Yet black Americans have only achieved formal equality in the United States, going from an internal colony to an internal neo-colony where a black bourgeois exists but the majority of blacks are found in a race to the bottom in the labor market and violently oppressed by the carceral state. The democratic struggle for black freedom did not end with the Civil Rights movement any more than it did with the Civil War. By refusing the fight for proletarian leadership in this struggle against racial oppression, Marxists will not only fail to unite the proletariat but fail to articulate an emancipatory vision for the world we live in.

- Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877. (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1977), 8-11.

- Ibid, 145.

- Ibid, 145.

- Ibid, 153

- Frank Girard and Ben Perry, The Socialist Labor Party 1876-1991: A Short History, 4.

- Ibid, 6.

- Ibid, 12.

- Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in the United States. (New York: Russell & Russell Inc, 1965, first published 1903), 212.

- Ibid, 295

- Ibid, 140.

- David Herreshoff, The Origins of American Marxism. (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1973), 14-15.

- Ibid, 168

- Ibid, 170.

- Oakley C. Johnson, Marxism in United States history before the Russian Revolution (1876-1917). (New York: Published for A.I.M.S. by Humanities Press, 1974), beginning pages.

- Ibid, xi.

- Ibid, 71.

- Charles C. Johnson, Origins of American Marxism, 72.

- Ibid, 73-74.

- Paul Buhle, Marxism in the United States. (New York: Verso, 1991), 35.

- Ibid, 36.

- Ibid, 21/

- Ibid, 50.

- Ibid, 50.

- Ibid, 52.

- Ibid, 53.

- Philip S. Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, 153.

- Ibid, 243.

- Ibid, 245-246.

- “Platform of the Social Democratic Workingmen’s Party of North America,” originally published in The Socialist [New York], vol. 1, no. 11 (June 24, 1876), pg. 4. Accessed at: http://www.marxisthistory.org/history/usa/parties/slp/1876/0000-sdworkingmensparty-platform.pdf

- “Socialistic Labor Party of North America: National Platform, Adopted by the First National Convention, at Newark N.J., December 26-31, 1877.”

Accessed at: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/slp/1877/plat1877.pdf - “Socialist Labor Party of America: National Platform, Adopted by the Twenty-Fourth National Convention, Henry Hudson Hotel, 361 West 57th Street, New York City, May 5-7, 1956.” Accessed at: http://www.slp.org/pdf/platforms/plat1956.pdf

- Philip Foner, The Great Labor Uprising of 1877, 178.

- Peter H. Clark, “Socialism: The Remedy for the Evils of Society,” originally published in The Cincinnati Commercial, July 23, 1877. Accessed at: http://www.blackpast.org/1877-peter-h-clark-socialism-remedy-evils-society

- For bio info on Sorge see Herreshoff, 53 – 106.

- Friedrich Adolph Sorge, “Socialism and the Worker,” Originally published in 1876, went through many editions. Text referenced is that of a pamphlet published by the Social Democratic Federation in Britain in 1904. Accessed at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/sorge/1876/socialism-worker.htm

- Oakley C. Johnson, Marxism In United States History Before the Russian Revolution (1876-1917), 72.

- Paul Buhle, Marxism in the United States, 51-53.

- Daniel DeLeon, “Restiveness Among Colored Workingmen.” Originally published in The People Vol. VII, No. 6, New York, Sunday, May 9, 1897. Accessed at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/deleon/pdf/1897/1897_may09a.pdf

- Daniel DeLeon, “Race Riots.” Originally published in The Daily People, July 30, 1900. Accessed at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/deleon/works/1900/000730.htm

- Werner Sombart, Why Is There No Socialism in the United States?. White Plains, NY: International Arts and Sciences, 1976. Print.

101 Replies to “Early American Socialism and the Poverty of Colorblind Marxism”

Comments are closed.